There’s a Spanish band with a peculiar name, La Oreja de Van Gogh. It’s a name that rolls off the tongue. La Oreja de Van Gogh. Van Gogh is pronounced* similar to how most Americans pronounce it, though with the accents on the vowels found commonly in Spanish. Ván Gó. Add on that slight Spanish lisp and the name really rounds out. La Oreja de Ván Gó. The translation into English is surprisingly straightforward, not guilty of double meanings or impossible translations: The Ear of Van Gogh.

The fact that I can say that and you know exactly what I’m talking about speaks to Van Gogh’s prominence and reputation. But it also belies an underlying issue in the conversation surrounding the great Dutch artist. For all that Vincent Van Gogh may be one of the most famous artists in all of art history, he’s still seen mostly as a poor suffering artist defined by his mental illness.

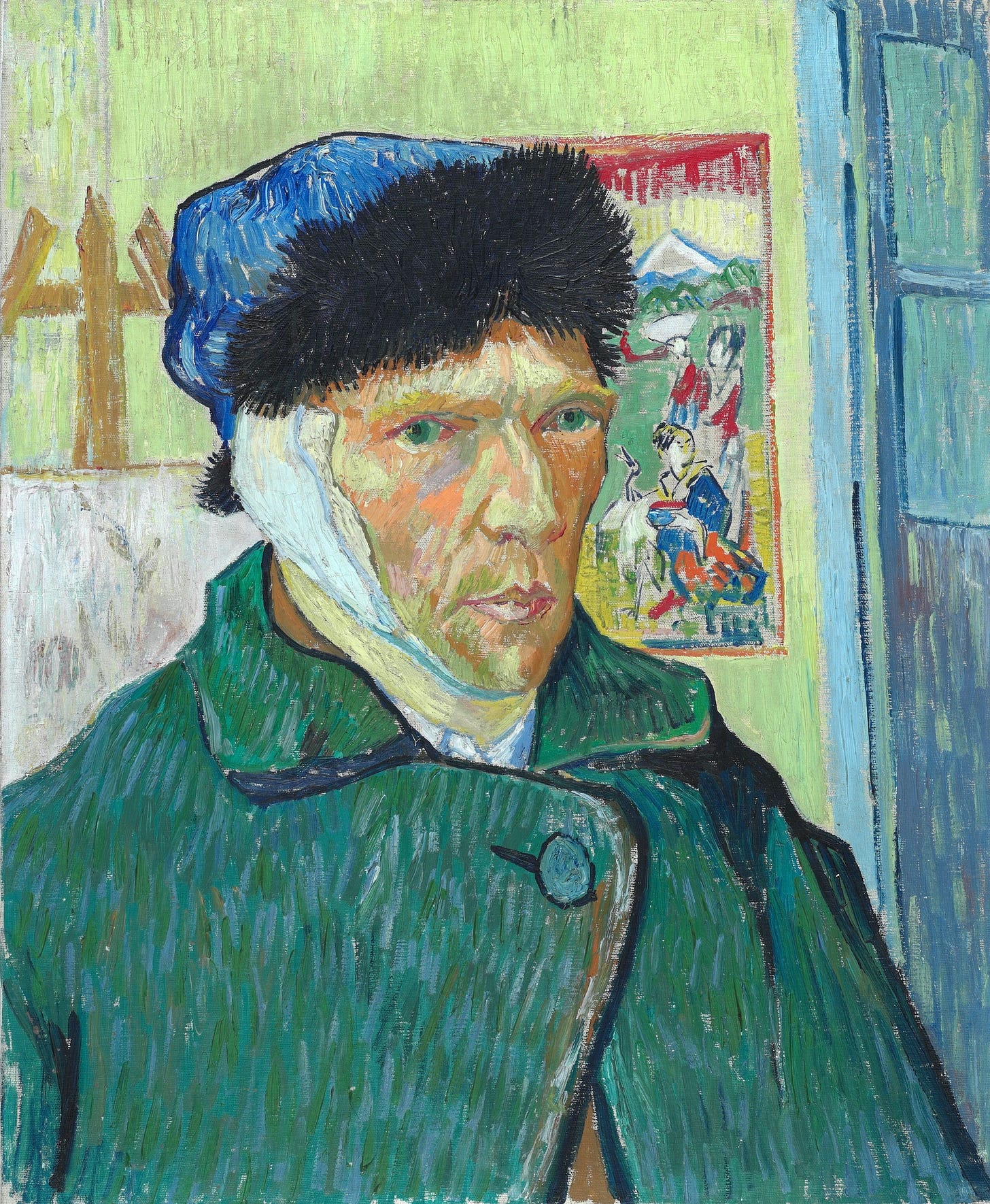

When we look at Van Gogh’s self-portrait following his alleged self-mutilation**, we seem to be teetering on the edge of something with him. Are we teetering on the edge of greatness or madness? Is this not how we’ve come to define Van Gogh? Yes, he’s the artist behind such iconic paintings as The Starry Night, but he’s also famous for losing his ear and giving it to his favorite prostitute.

It’s natural that from a public perspective, we would connect the dots here. Van Gogh had mental health problems and made this beautiful art, so they must be related. And it’s this shadow that has largely followed Van Gogh and streaked his reputation.

Vincent Van Gogh is not the first, nor the last, person to have his mental health color over his work. The American writer Edgar Allan Poe is often seen as a figure of darkness and depression, when in fact he was playful, athletic, and known to joke around with just about anyone and everyone. Yet, his complicated past, the manner in which he died, and the nature of this work have colored our perception of him and turned him into a persona more so than a human being with highs and lows.

Jackson Pollock also suffered a similar fate. He suffered from alcoholism for much of his life during a time when alcoholism wasn’t recognized as an illness. This cultural deficiency, paired with Pollock’s constant feelings of inadequacy, played a hand in his untimely death. That his death was also directly related to his affair with the much younger Ruth Kligman (the only survivor. Her friend died in the crash as well), has only added to the mysticism surrounding Jackson Pollock. Van Gogh is in this same vein.***

We cannot overlook Van Gogh’s Mental Health as it does have a large impact on his life, but we can demystify some of the romanticization surrounding it. The part that bothers me when we hold on to this false idea is that people tend to believe mental health problems are needed to make ‘good art’ which is absurd. I turned to my sister one day and told her I could tell how her mental health was doing based on one simple factor, which was whether or not she was creating. She gave me a haughty response, the kind you come to expect from a younger sister annoyed that her older sister hit the nail on it when she doesn’t want to acknowledge something. But it remains true. When she’s not creating, she tends to quietly confess to me she’s depressed.

It’s not that you can’t be creative when you’re in a low mental health state, but that low state makes it difficult as hell. I can’t write when I’m depressed. I can’t paint. I can’t draw. The motivation disappears, and it’s like a fundamental part of me has been locked away. I’ve known many people who struggle with their mental health, and not a single one is productive or able to create when in the dark valleys of their mental health. It’s not impossible, but it’s not a state that feeds into productivity. I realize, of course, there are always exceptions and this is not taking into account all illnesses, but I’m not in a position to speak on all of them to begin with.

What I mean to address is the misconceptions surrounding Van Gogh’s creativity. I cannot make a commentary on mental health. My knowledge is insufficient. But art, I can talk about art. Vincent Van Gogh’s Mental Health has been the subject of much speculation. I’m not going to diagnose him. For one, I’m not a doctor so I have no authority to do so. For another, it would be unfair to diagnose a man who has been dead for over a century based on the feeble bits of evidence I have at my disposal. For this reason, I’ll be proceeding with today’s post by simply referring to his Mental Health, not getting into specifics.

Before we go into his Mental Health in relation to his art, I want to set the backdrop for his lifestyle. First, it must be understood that Vincent was financially supported by his younger brother Theo. The relationship between Vincent and Theo was a vital part of both of their lives. You cannot have Theo without Vincent, and vice versa. Their relationship truly began with a walk in their youth when they tethered their souls to each other. This walk became a cornerstone of both of their lives, one they frequently harkened back to in their letters.

Theo was an art dealer, able to make enough money to support Vincent as a largely self-taught artist who was hard to sell. Before he pursued art and support from Theo, Vincent spent years seemingly lost, unable to find a career that spoke to him. For a time he became obsessed with religion and working for the church, but to the bafflement of his Victorian-era companions, his methods for preaching (essentially forcing himself into poverty like those he was supposed to be preaching to) were too unconventional. Unable to support himself, his parents often stepped in to help him with mixed results.

In a modern lens, it’s not strange that Vincent was lost. We all are. Like Vincent, I didn't paint until I was about twenty-seven, and I was wandering from job to job to figure myself out (I still am). But this wasn’t the 21st century. In the 19th century, typically people started working very young and stayed in their jobs for most of if not their entire lives. In Vincent’s late twenties, he was expected to have settled into a career and have already started a family to progress the Van Gogh name. Children were expected to reach ‘adulthood’ and ‘maturity’ as teenagers, and Van Gogh did not. His father was strict and religious, so naturally, he would not have been keen on Vincent’s behavior.

It also didn’t help that Vincent’s romantic life was often a mess. You get the idea that Vincent always wanted to save someone, to take in a poor single mother who worked as a prostitute as if he alone could fix her and make her life better. When you read these parts of Vincent’s life, it’s hard not to see what a tender-hearted soul he was, and how he could love the unlovable. His father was religious, but he was Christlike.

Added to that, city life often left its toll on Vincent. This, paired with the cost of canvases, paint, and brushes, also means that while he was not living in poverty the way we’re sometimes led to believe, he was often in need of money from his brother. That Theo was not married and without children for much of their lives also factors into his ability to care for Vincent (he would eventually marry and even have a son named Vincent). The anxiety of having Theo rely on him, paired with the fast-paced city life, was not conducive to a healthy mental state for Vincent.

On top of that, Vincent wasn’t just living anywhere. He was living in Paris, the center of the art world. Ever self-conscious, he was often uncomfortable with all the artists he found himself amongst. In time, he came up with a vision, an idea to create a community of artists in the countryside of Arles.

The Yellow House is legendary in art history. By conjuring its name, we’re brought to mind iconic paintings of Van Gogh.

Now my idea would be to furnish one room, the one on the first floor, so as to be able to sleep there. This [house] will remain the studio and the storehouse for the whole campaign, as long as it lasts in the South, and now I am free of all the innkeepers’ tricks: they’re ruinous and they make me wretched […] I hope I have landed on my feet this time , you know – yellow outside, white inside, with all the sun so that I shall see my canvases in a bright interior – the floor is red brick:; outside, the garden of the square, of which you will find two more drawings. I think I can promise you that the drawings will get better and better. - Letter to Theo Van Gogh, May 1888

This image isn’t singular to Van Gogh. Even I’m guilty of dreaming up a cottage to run off to and paint in all day. Escapism beckons all of us, social media is proof of this. Since I was young I’ve dreamed of a home akin to the Bennet household in the 2005 film. Except I’m a city girl through and through.

Vincent’s dream doesn’t stop at a house for him to paint in, but a community he could share a home with, a “Studio of the South.” He wanted to escape the pressure of city life and found the rural landscape was healing to his soul. Really, Vincent Van Gogh was the First Cottage Core Girlie (honestly if it wasn't for that band name I would have probably titled this “Vincent Van Gogh - The First Cottage Core Girlie” without reproach). Vincent started renting The Yellow House on May 1st, 1888 in Arles and set to work in preparing this dream home. It cost 15 francs per month and originally functioned as a studio alone. In September, he moved in.

What started as an optimistic time for Van Gogh soon went downhill. Like I said, he wanted a community. I don’t think it’s far off to suggest Vincent was a bit lonely. He needed companionship and criticism. So Vincent set to work on furnishing and decorating the Yellow House and even used his own work as decoration, including The Night Cafe, Starry Night over the Rhone, and The Trinquetaille Bridge. He surrounded himself with Japanese art, which was a major inspiration for him.

In the quiet of Arles, Vincent found himself healing and rebuilding as he put together his home and prepared for his first and only gust: Gauguin. The temperaments of both artists were so contradictory, and to have them in such a small space seemed to be asking for problems. Prior to Gauguin moving in, Vincent gained confidence in his work and found himself becoming more productive. When Gauguin left, Vincent had lost an ear, was hospitalized to the horror of his brother Theo, and would soon lose the Yellow House. Vincent would leave behind the Yellow House and take residence in Saint Remy, an asylum.

Soon after Gauguin leaves, we find Vincent at an all-time low, but most important to this is that he is NOT PAINTING. On December 24th, 1888 police found him suffering from blood loss and took him to the hospital. He became delirious during this time, going in and out of consciousness. Vincent couldn’t gather his bearings, and couldn’t comprehend where he was or what was happening to him. And people speculate that this Vincent, this man who was lost and confused, was painting the masterpieces admired in museums across the world?

Even when he left the hospital, very little art was worked on. Vincent would go on to be hospitalized multiple times in February of 1889. His third entry to the hospital was involuntary and the result of various complaints made against him. It’s important to note that in mid-March when Vincent seemed to finally be in recovery, he was not clear on what happened in the months prior. He couldn’t recount the previous months in great detail, or pinpoint exactly what happened to him.

In May of 1889, at Theo and his doctor’s suggestion, Vincent Van Gogh agreed to enter an asylum in Saint-Remy, located in a monastery of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole. He was originally supposed to go to a more public asylum in Marseilles but went with Saint-Remy where he stayed for a year. In that year, Vincent experienced four ‘episodes.’

Again, keeping this aspect of Vincent Van Gogh’s life in mind, it’s easy to see how he is often seen as an artist fueled by his own Mental Health, and how this persona he’s been defined by is so arresting. Vincent lived in a time where Mental Health wasn’t understood. I’m not sure it’s really understood now, more than a hundred years later. The care he needed wasn’t available to him, but still, he persisted in seeking help, in trying to heal so he could create. How compelling is that? How can we not instantly connect with that man?

In the asylum, as he was healing, Van Gogh continued to paint. It was in Saint-Remy that Van Gogh painted one of his most famous paintings, The Starry Night. I marvel at this as I look at the painting. Admittedly, when I look at the painting, I’m reminded of the hymn How Great Thou Art. I don’t think it’s strange that a song about the divine, a song that says, “I see the stars, I hear the rolling thunder” would connect me to Van Gogh. It’s not necessarily that I’m saying Van Gogh makes me think of God or religion, but that there is something incredibly divine about Van Gogh, something that cannot be denied.

There is an optimistic spirit to Van Gogh’s work, a hopeful quality that’s impossible to miss. To see this and insist he painted these visions of hope and optimism while in deep depression is to misunderstand both him and the art entirely. His stay and Saint-Remy allowed him kindness, to be met with the warmth he so desperately craved from a community he couldn’t carve out himself. Yes, I do think his paintings are a little lonely, but maybe I’m just seeing my own loneliness in them. But Vincent’s loneliness is the kind that has open arms, that offers you to come into his arms and break away from the loneliness with him.

I found myself thinking about that one episode of Doctor Who. I’ve never been a fan and can’t honestly say that I’ve seen one single episode, but even I know of the famous Van Gogh episode and the museum scene makes me emotional. In the scene, Vincent is taken to a museum where, unbeknownst to him, he is about to see an exhibit of his work. My favorite part of this isn’t the emotional scene where he overhears praise of his work. My favorite part is the way in which he meekly marvels at the art, needing to be yanked away by the Doctor. There is a curiosity in his eyes, a spark of awe. It’s so small, but it’s so very Vincent.

In his time in Saint-Remy, Vincent would go on to finish over 150 paintings. His healing, his time to rest from the weariness of the outside world, resulted in incredible productivity. It was in this time that we get some of the most incredible works of Van Gogh.

I’ve had Vincent Van Gogh heavy on my mind as of late, as I battle with my own mental health problems that are admittedly much smaller. My niece and I draw in the evenings, her for much longer than me. Drafting has always been my specialty outside of color selection. I tend to get bored after the drawing is done, and not as enthused to continue. Quietly, we sit together and draw, and I can feel a part of me being stitched together again.

At my lowest, during the Pandemic, when I felt my life was well and truly robbed of me, I couldn’t create anything. I couldn’t understand why I couldn’t use this negative energy to at least rant on the canvas. Why couldn't I just create? Why did I just feel terrible the whole time? I thought, foolishly, why can’t I be like Van Gogh?

It wasn’t until I read about his life that I saw my folly, that I realized I am like Van Gogh. I, too, need to heal so that I can paint. I too, need to escape the noise and care for myself before I can paint. I need to fill my well first, then let the creative juices flow.

When we persist with the ideology that Vincent Van Gogh, like many other writers and artists, created great work because of his Mental Illness, we’re only hurting ourselves. We’re only creating a false narrative that prevents us from taking care of ourselves first and foremost. Mental Health is difficult. Sometimes it feels impossible to understand. But to romanticize it for the sake of art isn’t just ridiculous, it’s damaging.

Out of curiosity, I looked up La Oreja de Van Gogh. I was under the impression they aren’t making music anymore. I was quite wrong. Despite my qualms about such an odd band name, I played their music. And I gotta admit, it kind of slapped. Vincent couldn’t have known that one day his actions would inspire a pop band from San Sebastián Spain, who would then be heard by a Paraguayan-Puerto Rican woman in America. He couldn’t have known that he would appear as a character in an iconic British sci-fi series. I wonder what he and Theo would think if they knew.

Luka many thanks for sharing this insight about creative productivity and mental health. The pandemic was stunning for a long and in a surrealistic way to me. Still.

Luca, what a sensitive essay, a fine and thoughtful look into the artist as a whole. Van Gogh was so much more than the sum of its parts, thank you for celebrating this.