*Mild graphic imagery warning*

I suppose my current hyper fixation isn’t that surprising if one were to pay close enough attention, though my family is baffled. I’ve tried to explain it, but my words fall on deaf ears as they stare at me as if to say, ‘did I ask?’ This isn’t to portray my family as cruel, just too baffled to function. You see, I’ve become insanely truly marvelously obsessed with Talking Heads.

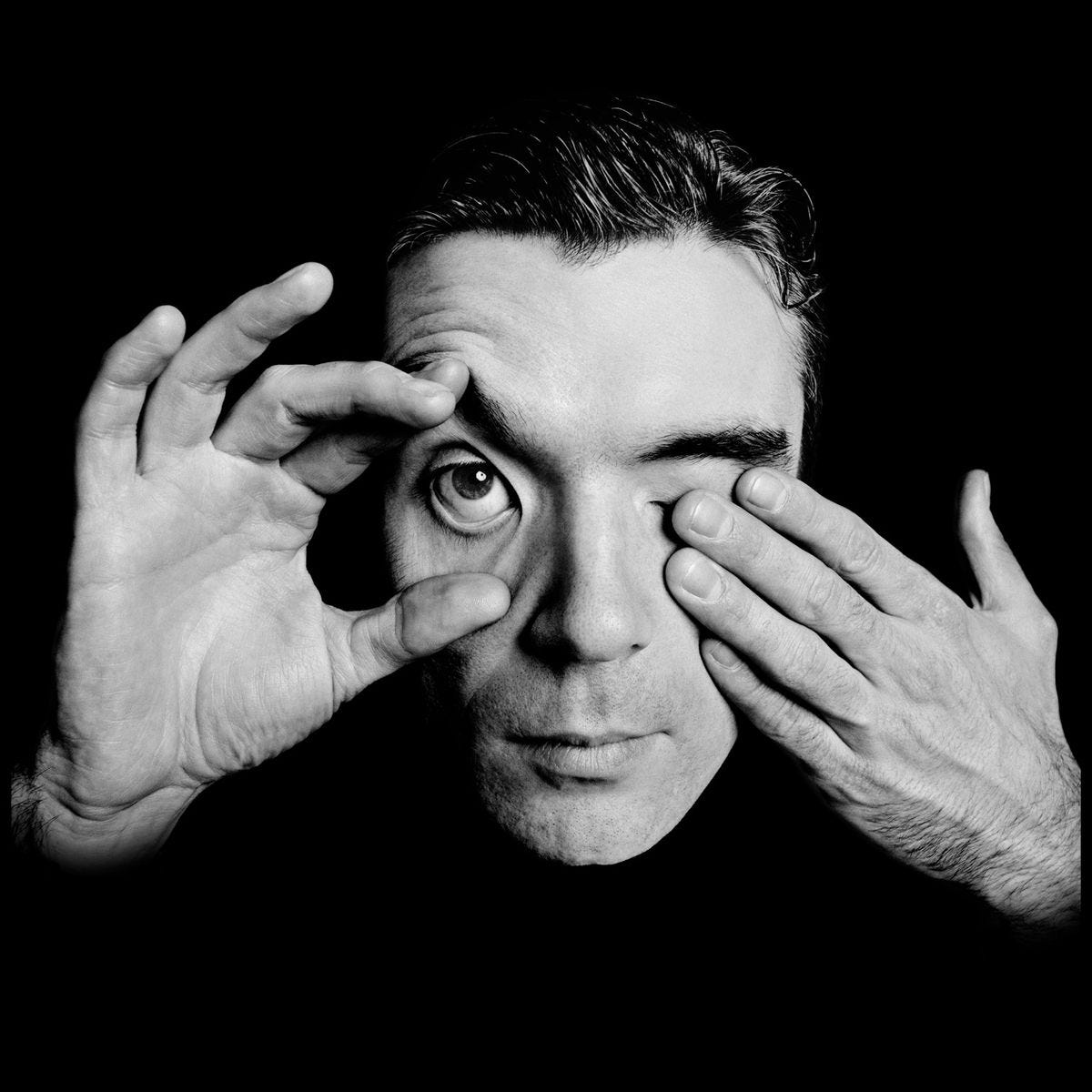

Before I lose you, this shouldn't really be a surprise to any reader of this publication. Talking Heads was a band from the 70s and 80s that was comprised of art students, and art is central to their work. That the face of Talking Heads (to the chagrin of the rest) is a dropout of RISD who has done photography, broadway shows, books, paintings, and even worked a graphic novel, is a testament to this. And encouraging.

But we’re going to take it back before I show off my growing Talking Heads vinyl collection or start arguing that David Byrne’s Bicycle Diaries is really art criticism and not a travelogue. We have to jump back in time before Talking Heads changed music. Because without a certain art movement, we may not have had the music of Talking Heads to begin with. They would have fettered out by Fear of Music, broken up so that Byrne became a solo act before their magnum opus of Remain In Light.

It starts with WWI. The brutality of WWI is I think lost on contemporary audiences as we tend to focus more on WWII. This is understandable given the jarring legacy of the holocaust and the imagery still prevalent today. WWII has long eclipsed every war in our minds, has weighed us down. We don’t talk about world leaders of the Vietnam War or the Gulf War the way we do those of WWII. People are still arguing over points of WWII, and some still deny the holocaust (I literally heard this at my last job).

What I need people to understand is that WWI’s brutality was new. My brother-in-law once described it perfectly as ‘a meat grinder.’ WWII’s brutality is of course undeniable, but it had The Great War before it. There was no Great War before WWI. At least, not to this scale. The echoes of WWI are seen in the works of the Lost Generation. I think sometimes there is a frustration over how schools have taught the Lost Generation (namely Hemingway and Fitzgerald) and we lose what is truly remarkable about the work of this time. I find the more I read them, the more I resonate with them.

When I read Hemingway for the first time, it was over a summer where I read books all set in Spain. I was fascinated with how outsiders personified Spain (which is to say: bullfighting) over how Spain personified itself (no bullfighting). Hemingway was a natural choice for this study, and I found what amazed me was how the plot just meandered, never seeming to really go anywhere except to follow the whims of the characters innermost desires. Yes, they are the Lost Generation, aren’t they? I found this same thing in Fitzgerald when I read him without the guidance of a teacher. They are one of the gifts that WWI has given us, and we’ve underutilized them. We fail to teach how this meandering, this almost meaningless text is exactly what we need today.

What the darkness of WWI has given us is still not fully comprehended. Much of art, music, and culture is bred from WWI. Why is that? I suspect in many ways WWI shifted mindsets on a mass scale. I remember hitting a shift, a sudden switch turning in my brain, when working on trafficking cases. There gets to this point where you see and read so much of the worst of humanity, that suddenly the world is shaded different. I’ve had to claw my way out of that, but it’s not fully gone. It never is. And I was sitting in a desk in an office, not in the trenches watching my fellow soldiers succumb to a slow horrific death.

It’s a bleak shift, an irreversible change in perspective. Suddenly, everything feels like spilled milk, utterly ridiculous. A coworker was lamenting to me about flags and politics that were utterly stupid. I cannot be kind about it. It was stupid. I cannot have compassion for spilled milk anymore. I find so many complain about mundane idiocies. There are days when I want to scream and shout SHUT UP SHUT UP THERE IS TRUE SUFFERING AND THEN THERE IS YOUR STUPIDITY SHUT UP SHUT UP. But, well, that’s not exactly productive. And I can at least recognize it’s not entirely true. This isn’t pain olympics. But it made me good at my job. You need that switch to help trafficking and asylum victims. I needed to become that person.

On the one hand, my perspective from this shift allows me to let go of things that might have made me angry before, on the other, my compassion for true darkness denies me compassion for seemingly small things. So when you hit that mindset, remembering of course my own experience is lighter to those who fought in the Great War or really any war, what do you create?

Nonsense.

You create nonsense.

Dada is an exploration of nonsense. That’s the best way I can define it, though it does not inherently wish to be defined. Where Surrealism sees its roots in the work of Sigmund Freud, Dada’s roots are in PTSD surrounding WWI and perhaps indirectly the writings of Nietzsche. I will not be getting philosophical as I lack the proper education at this moment. My limited understanding can only convey that my understanding of the famous Nietzsche quote “God is dead,” meaning: belief in God and the virtues that come with it have died and this will result in the loss of morality, would not be an unsurprising root for Dada.

Dada is most famous for the works of Marcel Duchamp. Understandably, his work is jarring but fascinating. We get the idea that he’s challenging us, daring us to oppose him on what is and isn’t art. Can we stand here and call this toilet art? And why not? Who are we yielding to by saying no? Who are we yielding to by saying yes?

I do not think Duchamp cares much what we think of it. Rather, I think he cares that we are thinking of it, that this is forcing us to confront ourselves in some manner.

And what do we think? What can we take from this nonsense? What can we build upon this? Is there anything to build upon? I could wax religious about this, but I’ll refrain there too (though I’m much more adept there), but I wonder what the mind can do with nonsense. I think it can do quite more than we realize. Maybe you’ve seen ads for those phone games that consist of rope tangled together, and to win you have to untangle it. The trick with these ads is that they’re designed for you to automatically fail. In that manner, they are nonsensical.

We’re perhaps drawn to these ads as a trick played by people intending to lure us in to purchase or download an app. But in some ways, Duchamp is doing the same thing. We may try to make sense of his work, and while we do this, he is off having fun with the other Dadaists. By trying to contextualize, we have already failed. By not contextualizing, we have failed ourselves. The brain wants an explanation, a story. It wants to make sense of everything, and Dada is asking us to let go of that.

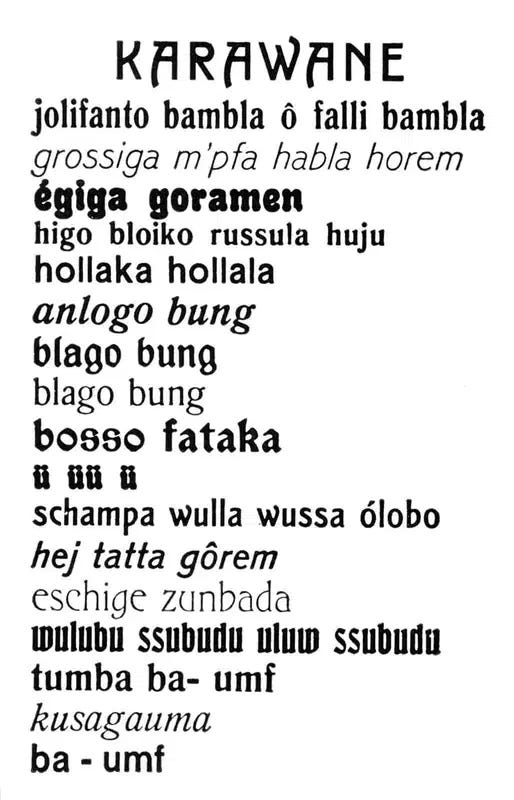

Dada by nature also messes with form, which is where Hugo Ball comes into play. I could argue here and now that Hugo Ball’s poetry is a parallel to jazz music, namely that of free jazz. I have no evidence to suggest free jazz was directly inspired by Dada, though I did find something from Rutger’s that may align with my thinking. (I’m going to ride the high of my own non-educated thoughts being similar to a thesis submitted to Rutgers for some time)* But the pattern, the ripple effect, is undeniable.

Hugo Ball was born in Pirmasens, Germany on February 22, 1886. Raised Catholic, he had a natural inclination towards the performing arts. During WWI, he tried to enlist but was denied due to medical reasons. I want to emphasize this is often a sore spot for men of that time. To be denied the right to fight was a heavy blow on one’s ego (See: Jackson Pollock), but the blow was softened when Hugo Ball witnessed the invasion of Belgium and became disillusioned with the war.

“The war is founded on a glaring mistake, men have been confused with machines.” - Hugo Ball

Now an anarchist that was hated by his country, he escaped to Switzerland where he opened a cabaret and continued to speak out against war. Ball opened the Cabaret Voltaire in February of 1916 in Zürich. While it didn’t last long, it proved to be fertile ground for a new movement. Ball encouraged artistic experimentation, pushing form and language beyond its limits.

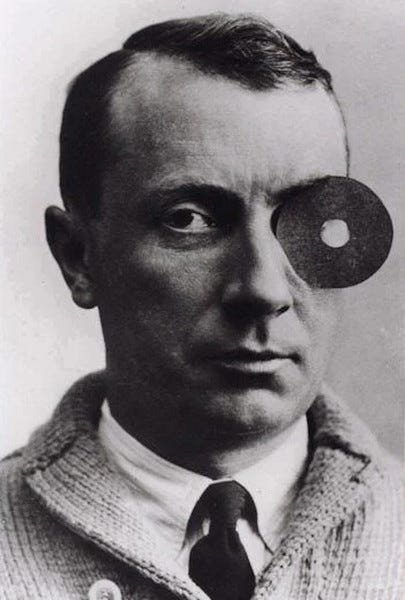

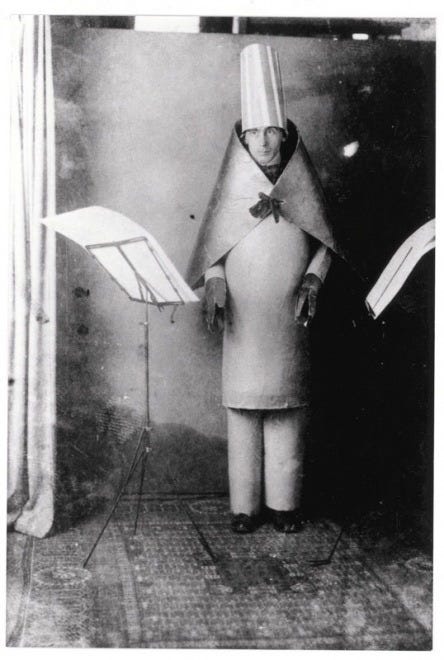

This leads us to Hugo Ball in a paper outfit reciting his nonsensical poetry. These jumble of words remind me of an Italian singer who wrote music with words that were not real but meant to sound English. Though Ball was German, some parts of his poems click in English. This jarring effect, one not entirely intentional, puts me in a strange stupor. Immediately, I catch some phrases that sound like English and make me want to understand. It is just like Adriano Celetano’s ‘Prisencolinensinainciusol’ which aims to personify what American English sounds like to Non-English speakers through gibberish.

Ball, however, was not looking to poke fun at Americans. His intent was to push back against the confines of language, to reject form, and to push the consciousness away from understanding. The world no longer made sense to Hugo Ball, so he would take that and push it back. He would tell everyone, ‘see? this is the world we live in’ no matter how much it hurt their brains. I recommend giving a listen to his poems.

I bring up Adriano Celetano for two reasons: the first being that it’s genuinely fun to listen to him. It’s strange, and gives me a similar sensation to listening to Hugo Ball’s poems. I keep thinking I’m just zoning out, but in fact it’s just gibberish. The second is because it’s a fun example of how Dada has bled into music.

It would be impossible to speak of the predecessors and influences of Dada without going into Surrealism, and I’ve spoken quite a bit on Surrealism. But I think Surrealism stands on its own. Yes, it’s literally an off shoot of Dada, but I think it departs far enough from it. Music has the opportunity to emulate Dada in a way that is new and evocative, while still honoring Dadaist roots.

If it isn’t obvious, I’m headed towards rock music. But we wouldn’t have rock music without jazz and I’m always happy to talk about jazz. What could be more Dada than Free Jazz?

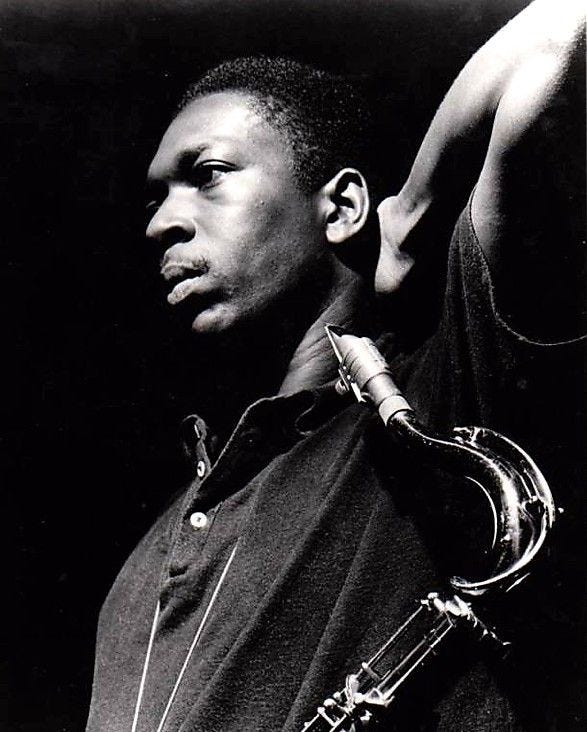

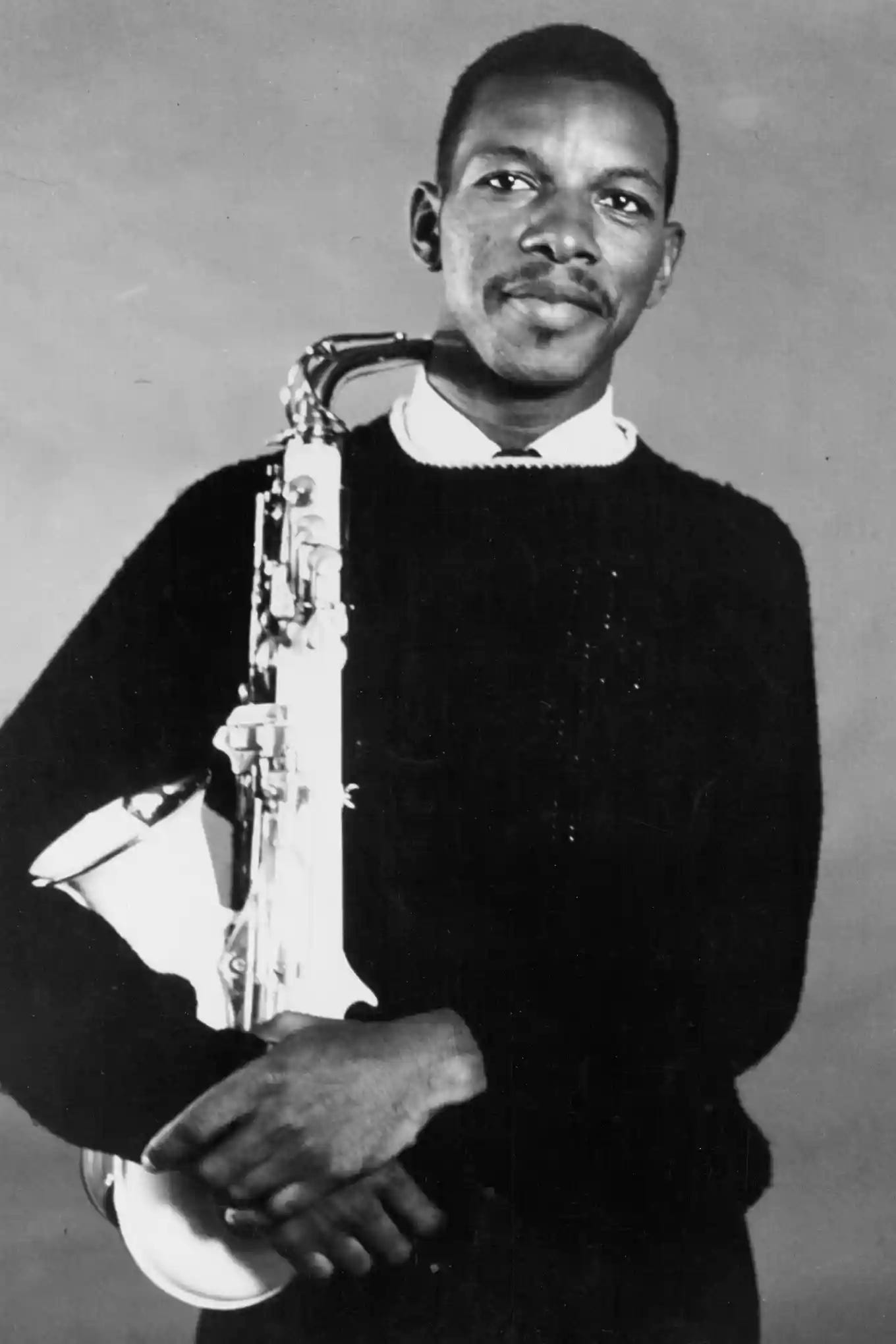

Free Jazz, when characterized by the works of John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman, is a push back from form and the confines of music - namely of Big Band Jazz. Big Band Jazz is in many ways the form of jazz that departed from mostly black influence and allowed for white musicians to have a choke hold on the genre. Think about it, when we name Big Band Jazz musicians, who are the big names? Artie Shaw (white), Benny Goodman (white), Glenn Miller (white) (and a personal fave), Henry James (white) (also an impressive one for someone to name), and finally Duke Ellington (black). I own multiple compilations of ‘The Best of Big Band Jazz’ and they all have one thing in common: Duke Ellington is the only black musician featured.

I personally love Big Band, and I don’t want to take away from many black Big Band singers that also had a huge impact at the time (Ella Fitzgerald, Etta James, Nat King Cole to name a few), but the most famous Big Band singer is, and likely will always be, Frank Sinatra. We should note many of these white musicians spoke out against segregation and in favor of civil rights. Sinatra went to white schools in his native Jersey to discuss the importance of integration and showing support for the merging of black and white schools in the state.

But I bring up this to help understand why John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman were fighting for a type of jazz that pushed back, that didn’t fall under the white gaze. Bill Evans is perhaps the ultimate personification of this. Evans (a white man) was a classical musician who merged jazz with romantic era music. The results are beautiful, and there’s a reason he was paired with Miles Davis and Coltrane in Shades of Blue, which I’ve discussed before, but in many way Evans personifies what Coleman and Coltrane were pushing back against. I say this as if I don’t have two Bills Evans records and they aren’t among my most played. What Evans was doing for jazz was incredible, just as what Chet Baker was doing for West Coast Jazz is undeniably good. They deserve their spaces in jazz history, but at what point does their space infiltrate the space of others?

The other key factor into free jazz is the state of America at the time of its creation. We have the natural push back on an American society that was trying desperately to conform and normalize itself after WWII, to present a happy perfect image that was far from the truth, and a people that were denying themselves the firm grip of PTSD. I’m generalizing, but this plus the rise of civil right, and a shift in the building of America that would lead to the rise of Pop Art, all lend to the mastery of madness that is Free Jazz.

So where Hugo Ball’s gibberish is a commentary on the cruel nonsense of a war that is unjustifiable starts, Ornette Coleman pushes against the cruel reality of being a black man in midcentury America in a genre was solely personified by the sweat of his people and now synonymous almost entirely by Old Blue. Where is the sense in segregation, in telling the black musicians they must take a separate entrance from their white counterparts in the same band? Where is the sense in a world where these same musicians now turn to the dark community of heroin for refuge? (and, in Coltrane’s case, sugar) (I have a somewhat funny story about that*)

Free Jazz does not want us to dance like Swing or Big Band. It wants us to sit with it, to let it work through us. Free Jazz feels like you’re reading Clarice Lispector, a constant challenge to everything you think you know and understand. You cannot casually listen to it, and trying to do so will automatically make you lose touch with it. I think this link, alongside with the obvious fact that Free Jazz defies convention and form, is what links it to Dada.

However, I do not think Free Jazz denies meaning the way Dada does. A Love Supreme is instantly contradictory to that, as is The Shape of Jazz to Come and particularly how it personifies loneliness. Perhaps it is in this way that Free Jazz is nothing like Dada, where the link may end and music’s connection to Dada would be severed and we would lose the incredible influence of Cabaret Voltaire with the world of music forever.

Or it would be, if it weren’t for I Zimbra.

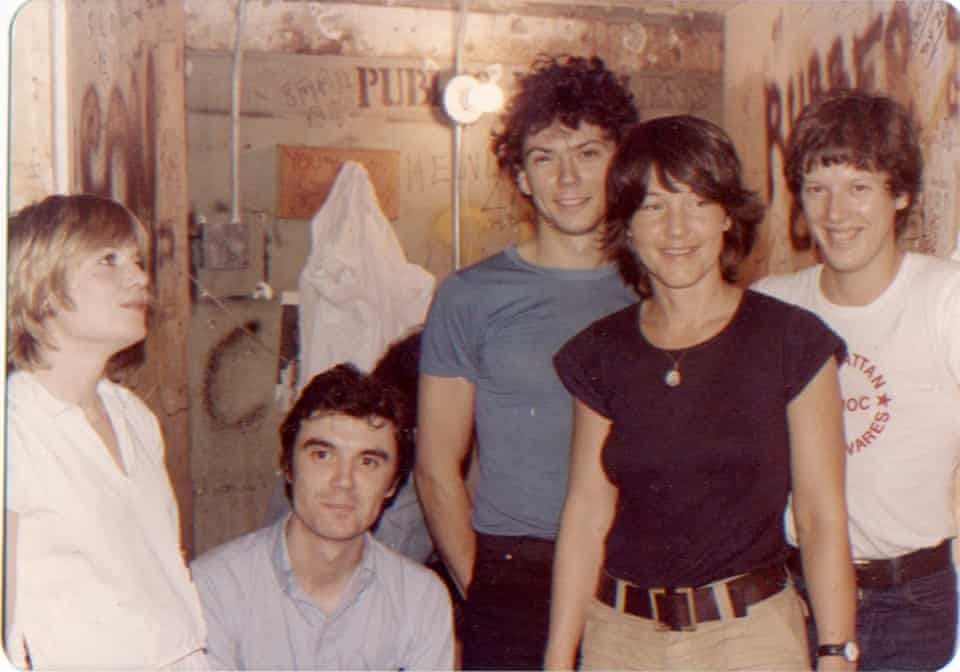

*cracks knuckles* Yes, it’s time to jump ahead to my soulmate David Byrne. Talking Heads started in RISD with Christ Frantz approaching David Byrne about being in a band with fellow school mates. His then girlfriend Martina (Tina) Weymouth was also asked to join but refused to because she felt being a girl would define her too much. They formed what was then called The Artistics before Byrne dropped out of RISD and moved to New York. Chris and Tina graduated from RISD and moved to New York, and once again the idea came up to form a band. It was mostly a cover band at first, and Tina learned to play bass and joined the trio. Eventually, they would add on another art student, Harvard graduate Jerry Harrison, as a keyboardist and backup guitar to Byrne.

They auditioned and became the opening act at CBGBs for The Ramones, and it would be Byrne’s second ever song Psycho Killer that would strike a chord most with listeners (and still does today!). They never took the idea of being a band seriously, never thought of fame. But, well, history decided otherwise.

CBGBs was the throne of Punk Queen Patti Smith. There she read poetry combined with music, and would eventually sing her seminal work from the album Horses. Patti Smith’s place in art history is nothing new, but many are unaware of her music career and how people like Patti shaped the world of punk. Horses, her debut album, is having its 50th anniversary this year (and I’ll be at one of her shows to celebrate!!).

The atmosphere of CBGB is purely punk in that it’s both the birth of punk through Smith and bands like The Ramones, but also the next stage of punk through Talking Heads. Punk music is the personification of the poor and unwanted parts of society that built up the old New York. I recommend reading Patti Smith’s Just Kids and Olivia Laing’s The Lonely City for a deeper understanding of what this means. But if not, there’s always the SNL 50th anniversary skit on the history of New York.

This isn’t the world of today’s tiktok New York, this is a world dealing with the aftermath of Vietnam, the failed promises of hippie culture as much as the failed promises of the 50s family life. We’re talking about a people and community wracked with shame and disillusionment, drug abuse and eventually the horrors of the AIDs epidemic. New York is bankrupt, Times Square is for porn and prostitutes, and CBGBs is gifted with Patti Smith’s poetry.

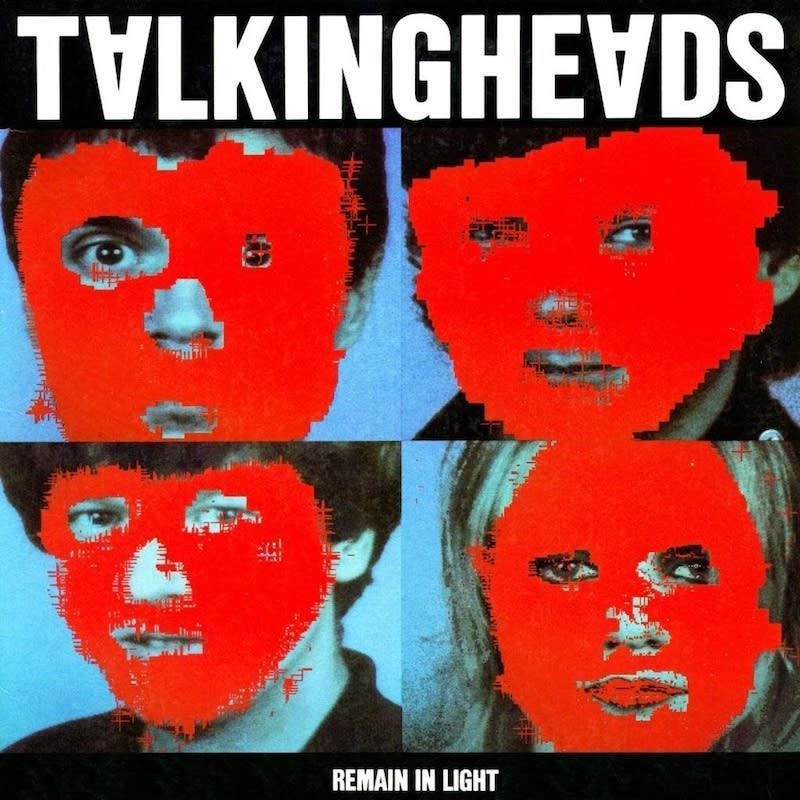

So you have these art students (all grads save Byrne) and they have no idea what they’re doing and start making music. Talking Heads would come out with two albums during this time, Talking Heads: 77 (where Psycho Killer premiers), and More Songs About Buildings and Foods (most notable for Take Me To The River). They would pair with Brian Eno on a three part legendary collaboration to work on Fear of Music. Up to this point, the music has largely been lead by David Byrne and would continue to be until Remain In Light.

I Zimbra takes a section of Gadji Beri Bimba and puts it to music, a suggestion I’ve recently learned started with Brian Eno. David Byrne was no stranger to Dada, and took Eno’s insights seriously. He understood Hugo Ball’s desire to remind the world that there were people of ‘independent minds.’ After all, Byrne himself is on the spectrum. We can see how this would appeal to him, latching onto something personal for Byrne.

The sound of I Zimbra, the very first track in Fear of Music, is instantly attention grabbing. It becomes clear this is not like other Talking Heads songs. If I didn’t know any better, I would think this was an African chant. That’s not without reason, Brian Eno was passionate about world music and shared that with the band, and this especially resonated with David Byrne (who has since focused on producing and sharing world music with the public out of sheer love for it). So it was in fact African music that inspired I Zimbra.

It’s a funky song, and doesn’t dare impress itself upon the listener. I Zimbra doesn’t explain itself. It simply is. The song doesn’t follow a traditional format, doesn’t contain verses, a chorus, or a bridge. It simply is, again and again and again.

I marvel at what Hugo Ball would think of his poem being put to music as David Byrne donned the oversized suit. Is the suit not itself reminiscent of Hugo Balls cardboard outfit? That this is also paired with Byrne’s signature dancing which has been described as nonsensical, seems in itself an additional ode to Dada.

Talking Heads were never accidental with their artistic influences. The cover of their second album is a reference to artist Andrea Kovacs. It actually reminded me of an Andy Warhol piece done meant to personify his friendship with Jean-Michel Basquiat. They even brushed shoulders with Andy at the Silver Factory. And they had Robert Rauschenberg design limited editions of their album Speaking In Tongues.

But it is this Dada poem and the song they wrote for it that changed the trajectory of their music and the music world in general. Jerry Harrison, keyboardist and eternally coolest person in the room, has described I Zimbra as his favorite Talking Heads song, but also the starting point to their next album Remain In Light.

Fear of Music came out in 1979, and as we enter the 80s so too do we enter a new form of music. Punk music had a bad reputation made worse by the AIDs epidemic. This put music producers in a tough spot, because they wanted to promote their music and make money, but calling it punk was a sure way to kill the music and prevent anyone from wanting to play it. But a new form of punk music was forming, molded by the arts rather than (frankly) angst. So they came up with a new name for it, a name that could pass censors and enter the mainstream: New Wave.

New Wave music and art are synonymous with one another. And soon it became synonymous with how we personify and imagine the 80s to this day. I Zimbra was not just a stepping point for Talking Heads as a band, but for New Wave music and 80s music in general. The use of ‘nonsensical’ words in their music came to characterize David Byrne’s singing.

The ripples of where I Zimbra and the subsequent Remain In Light lead are still felt today. The iconic 90s band Radiohead has openly stated Remain In Light and Talking Heads as one of their key influences. There’s a Selena Gomez song that uses a portion of Psycho Killer from Talking Heads. There’s a Simpsons Episode that features David Byrne writing a song with Homer Simpson. John Mulaney has stated David Byrne inspired his humor. And I’m just focusing on one example, not New Wave music as a whole.

I’m always amazed by how the Surrealist movement still has roots in pop culture to this day. I’m even more amazed by how Dada echoes into our world. David Byrne brought back I Zimbra with some minor changes for his work on American Utopia, his attempt to bring optimism during the mess of our current political climate in America. And he did this BEFORE the pandemic.

I think we crave nonsense more than ever today. No, I know we do. We crave the chance to lose ourselves, to be lost in escapism. Why else would we ‘doom scroll’ for hours? A family member confessed to me that when they get home they just sit on TikTok for hours. Another coworker expressed to me their love of reality tv because it takes them away from any drama in their own life. Several of my family members go into passionate rants about how they love to escape into the world of romantasy, to lose themselves in something. We do not want the world to make sense anymore, we want it to stop making sense.

What we want is the promises of Dada, Free Jazz, and Talking Heads. It’s like that TikTok that went viral early into the pandemic of the llama animation singing in a language I honestly cannot guess. It was suddenly everywhere. Did anyone understand it? Of course not. Did we care? Of course not. Nothing was making sense anymore, so we embraced whatever didn’t make sense.

I think we’ll find more examples of Dada rippling into our culture because I think we need it. I think we need to let go of things and get lost in the nonsense. I think we need a poem with gibberish, a Mona Lisa with a mustache, the promise of A Love Supreme, and a chanting song with funky beats.

At least, I know I do.

a note: I realized when I finished drafting this that David Byrne’s birthday was coming up and decided to move it up the roster. And, well, I’m a little in love with him, so here we are. I’ll confess now I could write an entire book about the artistic influences and history behind Talking Heads, so there may be more like these. Here’s hoping I can return to regular posting.

*As it turns out I’m almost done reading it and the evidence is exactly what I thought it would be! A win for Lu!

David Byrne also played with Brazilian musician caetano veloso at Carnegie hall

I got into Talking Heads a few years back because Timothy Chalamet worn several tees with them in Call Me By Your Name and I was intrigued. One of the best investigations I ever made. Love Fear of Music!

And I totally agree that WWI actually hits harder than WWII. I remember we read contemporary poetry in uni class, and at the start there was some patriotic, overexcited BS, and by the end you get Wilfred Owen, and this sheer bleakness sucks life of you. Of All Quiet on the Western Front (the book), where they all gradually die. Truly the world, the values, everything crumbled around them. Next to that, WWII narratives, despite all the tragedy, are somehow almost always carrying a ray of hope, there's always this resilience, there's reason, sense to all of this, which wasn't there in WWI. So, yeah, what else but Dada could come out of it.