Marie Laurencin's Sapphic Coquette Dream World

How one French artist built a world all her own

sub·cul·ture

/ˈsəbˌkəlCHər/

noun

a cultural group within a larger culture, often having beliefs or interests at variance with those of the larger culture.I asked in the past ‘What is girlhood?’ But a more long standing question still stands.

I have this porcelain doll that has been mine since I was a child. It goes with me to every place I live in, though not on prominent display like it did when I was a child. Much of this is because I’ve seen enough horror films to convince me that I must be kind to the doll, but wary. It’s in remarkable condition save one flaw, an imperfection in the eye that makes the doll appear to have a slight lazy eye.

The doll has perfect blonde curls, the kind even I covet. She wears pink frilly clothes with white lace, and seems in every way an embodiment of femininity. I didn’t care for Barbies growing up, and my younger sister was an ardent tomboy who was the original owner of a similar porcelain doll now lost in storage. I was captivated by it as a child, so on my subsequent birthday my parents gifted me my own. I’ve named her Key as she carries around a bracelet with a key.

Historically, dolls are the epitome of femininity in the world of toys. The aesthetics they present, whether it’s a Barbie doll or my porcelain doll, all harken to what we could debate as the ‘feminine gaze.’ The blockbuster film Barbie, for example, is full of the feminine gaze. Everything is pink, everyone loves and supports each other, and everyone is intelligent and capable. Of course, it’s not perfect, but the film is exploding with these gorgeous overtly feminine images. It’s a delight. Maybe it’s because I’m a woman, but I always find the feminine gaze is delightful.

Marie Laurencin is an excellent example of the female gaze in that she really did aim to make art that was feminine. The fact that this was in the early half of the twentieth century and her work is both unabashedly feminine and unabashedly sapphic is only scratching the surface, but it’s where we’ll start.

Laurencin was born in Paris France on 31 October 1883 to a single mother. She never knew her father and when she finally learned of him, he had already passed. This seemed to have no drastic effect on her, though it makes me wonder how much of her life was centered around women and lacking in men.

Her mother raised her in the hopes that she would become a teacher. While Marie Laurencin was intelligent, she didn’t make sufficient grades in school to justify a life in teaching, and instead at the age of 18 she studied porcelain painting in Sévres before continuing her artistic education at the Académie Humbert. It was there that she fell in love with oil painting.

While her early work was more realistic and seemed to stem from classical studies in art, she soon became involved in the world of the avante-garde. The biggest influence to her during this time was her friendship with Georges Braques, one of the founders of cubism. It’s often debated whether or not she is a cubist artist, but it would be unwise to say she wasn’t influenced by them.

She became romantically involved with the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, and is often seen more as his muse than the successful artist she was throughout her life. While this relationship was vital to both of them and inspired them both in their work, the most important relationship she had was with the fashion designer Nicole Groult, which would last forty years.

Despite that fact, she married the German Baron Otto von Waëtjen, which led to her losing her French citizenship and made her a German citizen. This was a bit of a problem, you see, as the Great War broke out. So what else was there to do? They fled to Spain.

While Laurencin had relationships with both men and women, her work largely focuses on both women and women loving women. Her paintings depict a dreamscape, a deep internal world of women and women and women. They are all doll like, porcelain dolls giving each other loving gaze. The paintings are often in pastel colors, though the colors became brighter in her later years (likely due to her failing eyesight). In a modern context, the best descriptor of her work would be “coquette.”

I want to start by explaining that I will be using the term ‘subculture’ because for the love of all that is good and saintly ‘aesthetics’ is ridiculous. It’s not the ‘goth aesthetic.’ It’s goth subculture. I have a deep deep deep love of subcultures and have since I was a teen myself. But back on track, what is coquette? Like most subcultures of today, it’s a trend born from Instagram and TikTok. I can admit internet subcultures like coquette, cottage core, and dark academia are lacking to what subcultures used to be. They seem more akin to fads, but one could make that same argument about variations within subcultures such as psychobilly, thrashabilly, punkabilly, surfabilly and gothabilly in the rockabilly subculture. But I digress.

The coquette subculture is in many ways a celebration of femininty, but with a dark and toxic touch. There’s a romanticization of Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov which definitely isn’t a terrible idea, and an undercurrent of dark mixed with pastel pinks and bows. I’m oversimplifying it, of course. Coquette is mostly found in Western cultures, though ironically Japan may have been further ahead of the train with past gyaru subcultures like the hime gyaru that was prominent in the early 2010s (though a quick google search seems to imply it’s still going and I’m not mad).

The most important factor of the subculture isn’t necessarily pink bows or romanticizing a book that definitely shouldn’t be romanticized, but it’s the celebration of that which is traditionally feminine. Never mind that most of the books deemed ‘coquette’ are written by men and by default cater to the male gaze. The best way I would sum up the look of the coquette subculture is simply: Angelina Ballerina, Marie Antoinette, and Lana Del Rey’s music. And I love all three of those things. I realize I may sound condescending, and I am with regards to the flippancy of TikTok subcultures, but frankly, I thinks it’s darling. I'll always be a sucker for fashion subcultures.

Subcultures serve many purposes, not in the least of which is the chance for individuals who live outside of societies standards to build a unique community. The Pachuco subculture of the 1940s consisted of teens of color who wore vintage of the 1920s, namely zoot suits. Not only where they outsiders because of their heritage and race (most were Mexican, but there were also Black and Filipino teens who wore the style), but they became targets of riots during WWII due to fabric rationing that dictated their style (and for many their inability to serve in the army due to their legal status) as offensive. Through subcultures, people who feel alone in a world they don’t automatically conform to can build community. They can build an internal world.

Where does Marie Laurencin play into this? You see, that’s exactly what she was doing. Marie Laurencine’s work is, by modern standards, coquette. She features pink ribbons, beautiful dresses, soft dreamy landscapes, and everything is feminine feminine feminine. But not only was Marie Laurencin painting her own dream world of women and beauty, she shared it with her community.

We tend to think of queerness in the past as depressing and sad. It’s not that this isn’t fair, we all know what laws were and have been and how queer people have been targeted and discriminated against for years. The problem is this narrative will leave out some of the joyful relationships and happy communities queer people were able to build in a myriad of situations throughout history. We can discuss the harms of the past alongside the joy, otherwise we are just erasing the happiness many experienced through history.

Marie Laurencin was not a hidden artist reviled for her queerness. She was up there with Picasso and Georges Braque, rubbing shoulders with them. Marie Laurencin was involved, admired, and revered during her time. Her work was even featured in the famed Armory Show of 1913. Her work was largely exhibited and beloved. She was able to be selective of who she painted commission of, and even painted Coco Chanel! Coco Chanel hated the painting, but Marie Laurencin refused to repaint it so she kept it.

What’s particularly fascinating about Marie Laurencin’s work is the art she came to be known by largely came in a somewhat lonely time in her life. As stated, her marriage to a German was a bit of an issue for her, so they escaped to Spain. Here we see her work transform. While she was involved with the art world in Spain, the world she built up and loved was in Paris. I don’t think it’s a stretch to say she was lonely.

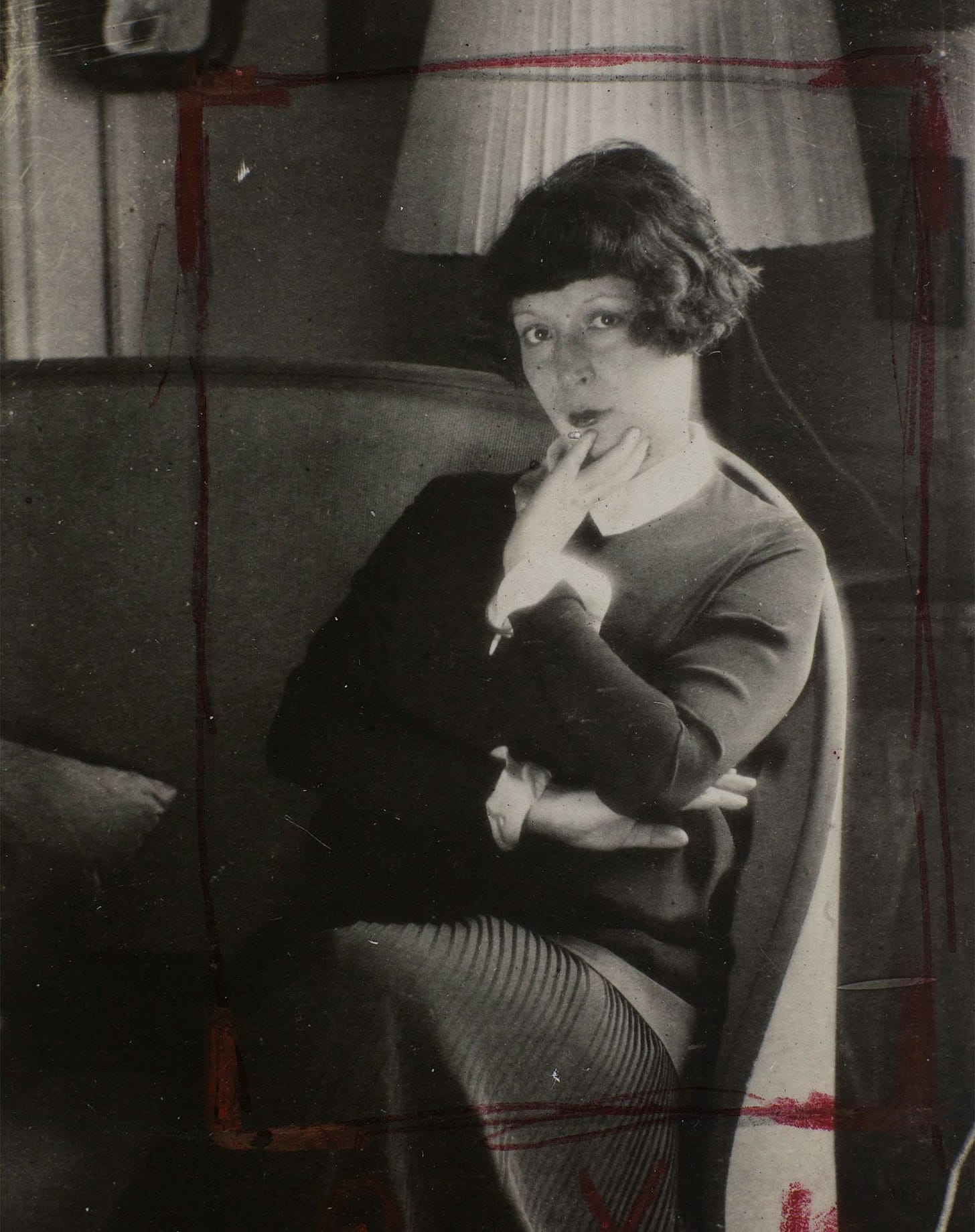

Below we see an early example of her art style taking form. The pink curtains were in fact chainmail, implying this beautiful woman is a prisoner. Perhaps Laurencin felt trapped in Spain and in her marriage. Her long time lover, Nicole, would come to visit her in Spain. Some see this and her social circle of Spanish artists as reason to negate her loneliness, but you can feel lonely in a crowd of people you love. I think, in the end, Laurencin knew Paris was home, and home was where she wanted to be. She filed for divorce on 1918 (she and Otto remained lifelong friends despite this), and returned to Paris on 1920.

In her time away, her art started to form into this dreamy world she alone crafted. There was no one else painting like Marie Laurencin, so she existed in a plane all her own. Do you realize how incredible that is? Yes, we all know Picasso, but a lot of people were trying to be Picasso, which can drown out his value (it didn't, but it can). No one was painting like Marie Laurencin, and no one could, and frankly no one has since. She was so unique and so far ahead of everyone else, not in the least because of how it can connect with teen subcultures in 2024.

Marie Laurencin’s work is in conversation with itself. It reveals a world and story, shedding the patriarchy in favor of Marie Antoinette’s Le Petite Trianon. She largely features animals with her dancers and musical women. But often there is symbolism used here.

The dove, frequently featured in her work is symbolic of her romance with Nicole. In love letters, they agreed to the symbol of the dove to represent their ardent love for one another, and so it graces her paintings in devotion to Nicole. And this isn’t quiet devotion. Marie Laurencin painted herself with Nicole in a loving embrace. She does not hide her sapphic imagery, but embraces it.

We know that Marie Laurencin was active in the queer Paris community in her time because she worked on costumes and set design for the ballet Les Biches. The ballet featured a main character known as Garçonne, who appears as an androgynous character in the center of a love story. The ballet also features two girls in gray who appears as lesbians at the end of the ballet. It was a queer production, a celebration of the people who made of the queer community in Paris. Even the title, Les Biches (The Does), is slang for lesbians. And Marie Laurencin was an active participant.

By understanding the social nature of Marie Laurencin, and that she took part in uplifting and supporting queer art, we can further see how her work isn’t just fanciful pretty work but an extension of her community. She is not only showing us her dream world, but she’s showing us the world she’s crafted with the people she surrounds herself with. It’s clear that she treasures this community.

I worry that subcultures today lack this sort of devotion and depth. I grew up in the age of scene kids, a subculture I wasn’t part of, but whom all of my friends were. Well, that and the goth subculture. My reason for not immersing was not lack of desire, but lack of funds. My art was often my was of expression, and in time I found a deep love for various subcultures, including foreign ones. But, I do believe the essence of what Marie Laurencin was doing is well understood today.

In researching for this piece, I naturally went down the Pinterest rabbit hole of ‘coquette’ when it hit me: Pinterest boards are like Marie Laurencin’s paintings! Even my own Pinterest boards of guilty of this. I was looking over these pins that collectively form an image. You can blur you eyes and get the idea: petals, cherries, pink ribbon, short skirts, pink underwear, delicate florals, ballet. There is a world being crafted on these boards. I realized I got it all wrong, that Marie Laurencin was just the original Pinterest Girl.

Following her death in 8 June 1956, and despite her popularity throughout her life, Marie Laurencin fell into obscurity. In an odd twist of fate, a museum dedicated to her in Tokyo was opened on her 100th birthday thanks to an ardent collector of her work (I heard a cute story about why he collected her work*). The museum was the first to ever be dedicated to a woman artist.

I think now is Marie Laurencin’s time. The coquette subculture will disappear, and Pinterest boards will be ignored, but I believe there will always be an audience ready to lose themselves in the dream world of Marie Laurencin.

Beautifully written and inspiring 😍👏🏻 Also, you made me discover a new woman artist, so I'm super happy! Thanks 🩷