“Art is how we decorate space, music is how we decorate time.” - Jean-Michel Basquiat (a man after my own heart)

If you haven’t figured out by now, I looove Jazz. I mean I’ve written about it so it should be obvious. And, as should be especially obvious, I love art. So if we took both of these things and put them together, what do we get?

We get Jean-Michel Basquiat.

I have a firm belief that you cannot appreciate Basquiat’s work unless you look at it while listening to jazz, especially Charlie Parker. Bebop came into prominence in the jazz scene in the mid 1940s - the height of the Big Band era which saw jazz become a largely white led music genre. This was also the era that saw the rise of Frank Sinatra, who would go on to be one of the most famous jazz singers if not the most famous jazz singers. Me being me, I love all of it. Give me Miles Davis. Give me Charlie Parker. Give me Frank Sinatra. Give me Billie Holliday. Give me Glenn Miller. Give me Laufey. It’s jazz? It’s good to me. BUT, it’s important to understand how much of the legacy left over in mainstream culture today focuses on the white jazz musicians over the more technically advanced black musicians.

Jean-Michel Basquiat wasn’t just aware of this, he lived it. If you’ve been with me for some time, you may recall that once upon a time I gushed like a child over a Basquiat painting of him and Warhol. It might be my favorite of his work, because there’s such an incredible energy to this piece. But I don’t know that I can pin down exactly one Basquiat that holds my heart the most.

My introduction to Basquiat wasn’t Beyonce posing with his work and Jay-Z’s semi-cosplay of the late artist (which I have mixed feelings about) (on the one hand… a reference to Breakfast at Tiffany’s. On the other, really? An ad?), but a video clip of an interview of him. I knew of him by then and was rather familiar with his work, but I accepted that it hadn’t hit me yet and one day it would. This video was when I really saw Basquiat. I can’t find the interview, but it was on a tv show where Basquit was told his work was ‘beastly.’ I was baffled by the comment the interviewer make, and evidently so was Basquiat, looking out into the crowd in bafflement, as if to say, “Are you hearing this too?”

Quickly I went down a rabbit hole, at work no less. I had to slip away to the bathroom because I got emotional over his work. And yes, I put on jazz while I scrolled through his paintings. How does he do it? How he paint the one thing that feels impossible - music?

There is to this day only one other artist I believe has matched Basquiat in this format, and that’s Gustav Klimt. Maybe I’m biased as I deeply love both of these artists, but I see them both as accomplishing something I cannot see anyone else matching.

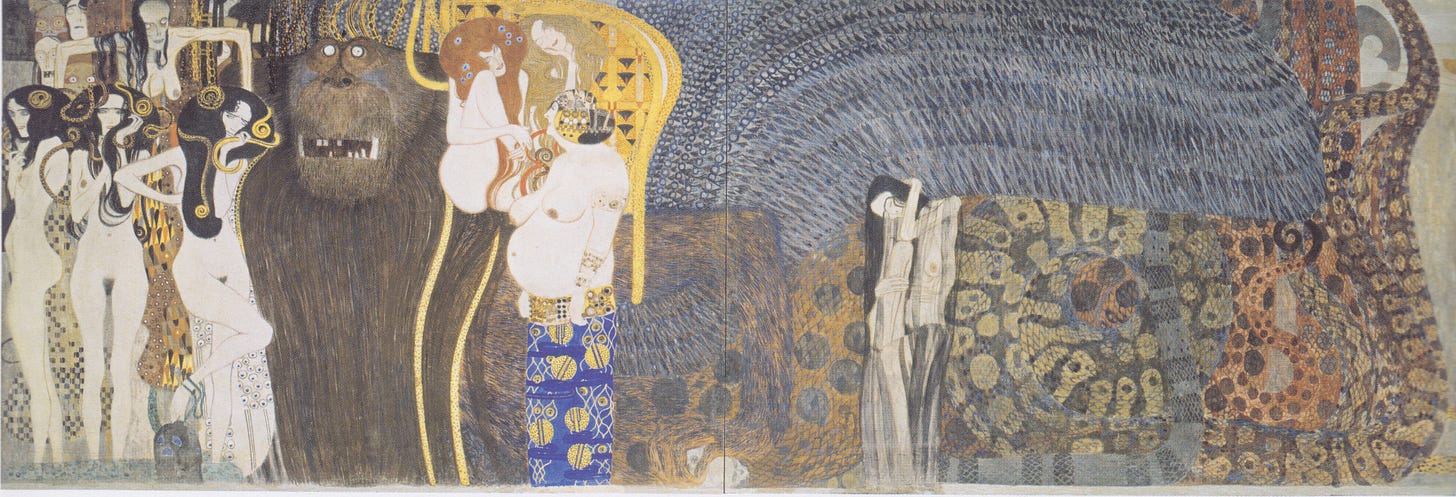

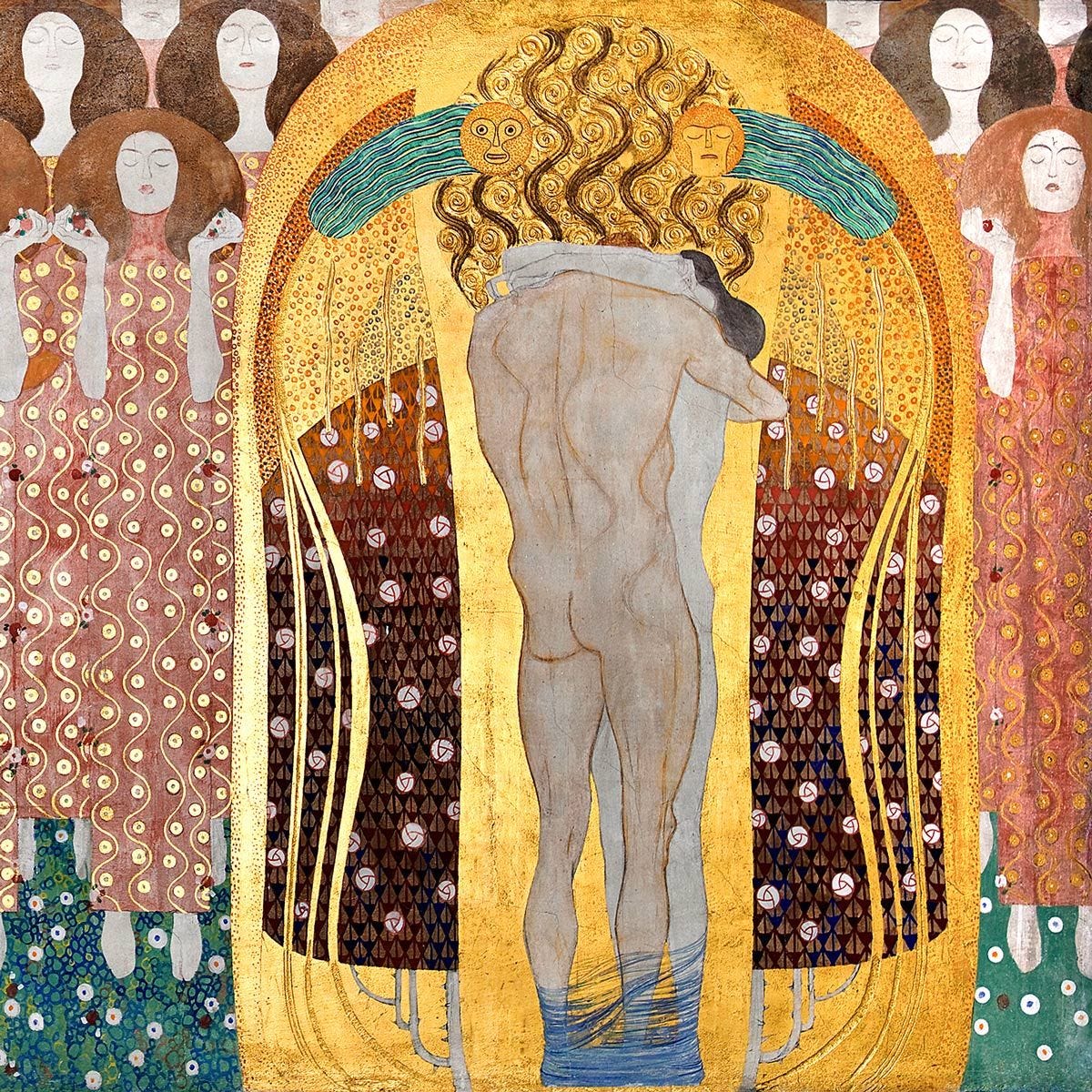

In 1902 Gustav Klimt premiered his Beethoven Frieze for the 14th Vienna Secessionist exhibition. The piece is meant to celebrate Beethoven, taking direct inspiration from Richard Wagner’s interpretation of Beethoven’s Ninth symphony. If you want a real gem, I found in my research that Brittany Broski is a huge fan of this piece and did a video on it! She honestly does a lovely job explaining the piece and sharing her own analysis.

To paint the work of a composer so famous I, with my minimal knowledge of Classical Music, recognize his name and work right away is no easy feat. Klimt, however, seems the best choice for this. I cannot imagine Picasso doing what Klimt did, or Matisse or really anyone else.

The piece is telling a story of the song, ending with a lover’s embrace. It’s the tiny details of this painting that we find all over the internet, the characters unfolding to us as the piece wraps around the walls.

Brittany makes the comment that she believes the piece should be viewed while listening to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, and I firmly agree. On it’s own, it’s incredible, drawing you in as only Klimt can. Klimt paints like he's seducing you, softly beckoning you to come closer and soak in his work. In this way, he suits Beethoven perfectly. His use of gold adds to the grandeur of his work, and grandeur is just what Beethoven deserves. But as you look over, you also get a sense of the whimsical. You’re taken somewhere strange, maybe even frightening, but always exciting and intoxicating. Who better to paint this than Klimt?

I’ve seen many piece of art inspired by music and musicians. If you go on Pinterest and look up any artist, you’ll find graphics, illustrations, posters, and even paintings inspired by their work. A personal favorite of mine is to scroll through the hoards of pieces inspired by the album Electra Heart (which I spoke of in my last post). But there’s a difference between a piece inspired by or depicting fan art of music, and painting music. Klimt managed it with Beethoven. I don’t think most people can. Except Basquiat.

Basquiat was unabashed with his jazz influences. He carried around the autobiography of Charlie Parker everywhere he went. While he was influenced by the music of his time (he even dated Madonna), jazz had the biggest influence on him. I like to think that this is something he and I share, as well as our Puerto Rican heritage. In The Lonely City, Olivia Laing goes on to explain just how much Basquiat loved and respected jazz musicians upon discovering that Billie Holliday did not have a proper grave:

“Basquiat was not unlike his hero Billie Holiday. Like her, he was dogged no matter how famous he became by racism: mistaken for a pimp; refused entry to smart parties; unable to even get a cab to stop on the street, but forced instead to hide while white girlfriends did the hailing. His exquisite, inscrutable, magical art was set against all, formulating its own deliberate language of dissent, creating a spell of resistance, speaking out in a rebellious tongue against systems of power and of malice. No wonder he was haunted when he discovered that Holiday didn’t have a gravestone, spending a consumed few days designing one to suit her: an object that would rightly mark the manner of her living and the manifest cruelty of her death.” - Olivia Laing “The Lonely City” (emphasis added)

I’ve tried to research this to no avail. It seems he never did succeed in making the gravestone. The closest I’ve found is a joint effort between him and Warhol on a piece about Billie Holliday. But this speaks volumes of Basquiat, both of his love for Jazz music and musicians, and how it is impressed into his work.

I have a special request.

Either while reading this or after, pull up the music of the jazz musicians mentioned. I’ll provide a list in the end, and listen to them while looking at the art shown in this post. Really sink your teeth into the music, pay close attention, and ask yourself how Basquiat is taking that and putting it on the canvas in ways never seen before, and never seen since. Okay, back to the post.

Let’s go back to Bebop. Bebop, which precedes Cool Jazz and Free Jazz (which I talked about in a gushing post recently), is all about improvisation. But it’s also a challenge to the listener, pushing away from the Big Band desire to dance. This isn’t music you dance to. It’s not music you can digest easily, which was its intent. It requires work on your end, and is in many ways the antithesis to modern pop music. Bebop was born out of the need to pull away from the growing popularity that started to work against black musicians in the jazz movement. Charlie Parker was its leader.

“One of his [Parker’s] goals in ushering in this new wave of bebop players was to put a stop to the whole ‘you gotta entertain me, you’re a Black jazz musician’ thing,” says Martin. “Basquiat was consistently aware of the racist ways in which he was being pigeonholed, so he found a lot of parallels between his treatment as an artist and that of his jazz heroes.” - Terrace Martin for The Broad on Basquiat’s music influences

Improvisation was a heavy theme within Basquiat’s work, but I would argue the biggest impact was his desire to not make his work digestible. Basquiat took from many influenced that centered on his background. He was a Black Caribbean American, half Haitian half Puerto Rican. That alone is a complex web of identity, something that cannot be simply stated as Black. I find it frustrating when people don’t talk about the Caribbean identity evident in Basquiat’s work when sometimes it seems to be screaming out of the canvas, but ironically I have to do the same here. How do you take a complex identity and saturate it to appeal to the masses? Well according to Basquiat, you don’t.

In the piece I gushed about on Notes, it’s been argued the painting was done in less than an hour given how fast he painted it and handed it to Andy Warhol. In fact, Warhol commented that it was still wet when he received it. Fast movement and fast brush strokes are a heavy characterization of Basquiat’s work, not unlike the incredible horn playing of Charlie Parker.

There are some strong parallels between Basquiat and jazz musicians. He, like many jazz musicians, was a heroin addict. He would go on to die of a heroin overdose at the age of 27, a loss that still shakes the art world to his day. Charlie Parker died at 34 of health problems made worse by his own heroin addiction. There’s something eerie about Basquiat dying only seven years younger than his hero, and of nearly similar causes.* You could almost wonder if Basquiat’s approach to heroine was similar to that of Bill Evans, a need to feel closer to his jazz heroes. But I can only speculate on that here. And that would be a gross oversimplification of the complicated life many face in drug addiction.

There is also the fact that Basquiat’s work is literally in conversation with jazz and jazz musicians. The Horn Players depicts Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker. Basquiat often used word play in his work, forcing us to interact with it and process it. Take a look at the painting. We see Dizzy. But where is Charlie Parker? Ornithology - the study of birds. Ornithology. Ornithology. Ornithology. Ornithology. Charlie Parker’s name is crossed out multiple times, even painted over. Ornithology is the name of a Charlie Parker album, further cementing his title as Bird

The words thrown around also point us back to jazz. They remind us of scant, the vocal improvisation found in jazz. In middle school I joined select choir because evidently they were desperate for people. I couldn’t read music, couldn't sing well, and didn’t know I was actually a tenor. I was put in Soprano. We sang a jazz song because my choir instructor loved jazz and was a jazz drummer (I inherited my love from her), and she taught of to scat a song.

Fu Dat Doo Dat Daa! Fu Dat Doo Dat Dat Daa! Da Ba Doo Daaa!

It’s the part of the song I remember most, because it felt so weird. We had to make it seem authentic, an impossible feat for a bunch of middle schoolers with meh voices. I didn’t “get” scat until I was sitting at a Jazz bar one night and they turned off the jazz music for a live musician who then sang “What Does the Fox Say” and used the weird sounds as scat. It suited his voice and the song perfectly, and I thought, “Oh! That’s what it’s supposed to sound like.” And now I see Basquiat paint it and I cannot help but think, “Oh! That’s what it supposed to look like.”

As a sign of intimacy, Basquiat includes the words Chan and Pree, a reference to Charlie Parker’s family. His three year old daughter, Pree, died of pneumonia, which sent Parker on a downward spiral fast. Chan was Parker’s wife. In sharing their names he’s declaring himself as in, intoned to them on an intimate level, while also sharing the names of two individuals largely lost to history.

Many motifs of Basquiat’s work harken back to jazz. There is his use of crowns, perhaps inspired by the likes of Count Basie and Duke Ellington, whom he loved. Not only were these two black jazz musicians who took on names associated with royalty, but there is something to be said about the courage to take on a title when the world is ready to spit on you. Both Count Basie and Duke Ellington went on to become jazz legends that uniquely shaped the genre. Duke even made an album with John Coltrane!

There are many possibilities for why Jean-Michel Basquiat was attached to the crown motif. My personal thoughts are that it started as a nod to the Duke then turned into a form of self love and recognition.

And then we get to this final piece. King Zulu for me has always been the oddest of Basquiat’s work. Perhaps its because it feels so simplistic by comparison. Here we see multiple jazz musicians referenced (some of whom are new to me!). Bix Beiderbecke, Bunk Johnson and Howard McGhee were the primary influences for King Zulu. Alongside that is a face inspired by Louis Armstrong. All of these aforementioned musicians were trumpeters, and here he is referencing the King of the Zulus in the New Orleans Carnival Parade. According to Louis Armstrong, who once participated in this parade:

“The Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club was situated in the neighbourhood that I was reared… And no place that I’ve ever been could remove the thought… that, someday, I will be the King of the Zulus… I won it in 1949... Wow.”

Basquiat choices here are very careful. He places his own King Zulu at the center of the canvas, then covers the canvas in blue to harken back to the cool tones of the blues. We are thrown into a sea of blue and emotion, but our King Zulu is smiling at us, giving us a chance to escape the blues. We are drawn straight to Armstrong’s smile, his promise that he, our King Zulu, will deliver us.

I wonder how many times Basquiat listened to jazz hoping it would deliver him, whether that be out of addiction, racism, loneliness, or poverty. It’s clear as day not just that Basquiat loved jazz, but he knew jazz. Basquiat knew jazz with the intensity of several stadiums full of Taylor Swift fans. And he expressed that knowledge and passion on the canvas the way no one else could and has been able to since.

”I wanted to be a jazz musician, but I couldn't play anything. So I became an artist, and my paintings became my music.” - Jean-Michel Basquiat

While I haven’t been the biopic depicting his life (or any artist for that matter), I personally enjoy the video depicting Jean-Michel Basquiat painting to jazz music. It makes me think we’re something like kindred souls, both in love with a music beyond our reach, both painting as we listen.

I’ve often wondered how I would paint jazz. How would I draw it? I’ve seen photographers nail what I think jazz feels like, but outside of Basquiat, nothing hits the spot. Nothing sings the way Basquiat does. I can look at his work and hear Billie Holliday. I hope I’m wrong, and that someone else will create jazz on the canvas. But if I’m not, then every time I pull out another jazz record, I’ll find myself thinking of Basquiat again, and about the incredible possibilities of art.

The incredible thing is that we haven’t even scratched the surface, nor have we spoken of how Basquiat has influenced music himself. But I suppose that’s a post for another day, eh?

Jazz musicians from my readings on Jean-Michel Basquiat’s influences: Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Billie Holliday, Charles Mingus, Dizzy Gillespie, Lester Young, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Bix Beiderbecke, Bunk Johnson, Howard McGhee, and Louis Armstrong

What a great article.

As a lover of Jazz music too (though perhaps nowhere near your own level in that respect!) - there are all kinds of things I want to reference here.

But I fear this comment would then become far too long. So instead, I just want to say that, as always, your passion and your way of writing about all of this is so engaging - it really is an absolute pleasure to read.

This is enchanting! Also so thoroughly researched and I could feel how connected you are to the subject. I loved reading it, thank you for writing!!