Today’s post is going to be heavy. I’m going to discuss art, domestic abuse, death and violence in detail. There will also be uncomfortable imagery involving blood and depictions of violence.

I will be sharing stories and insights from my time working with domestic abuse victims at an Immigration Law Firm. Please be warned.

I first heard Cherry Wine during a night that would become tradition. I was with my two best friends, Fox and Spence, at their apartment on a Sunday night. We made tea, Spence would play classical music on his record player. But this time Fox wanted to show us a song. The song was Hozier’s Cherry Wine. I loved the song instantly, taken in by the melancholic tone. But it would be years before the song truly impacted me. It would be years before I learned the true meaning.

When a new coworker would start in the team, I had to sit them down and have a serious talk with them.

“You’re reading about domestic abuse,” I’d say bluntly. “Later, you’ll take on trafficking cases, and it’ll be months before you can touch asylum. In the beginning, we’ll give you the lighter cases. But you need to learn to cope with what you read. These are real stories, first hand accounts. If it’s too hard for you, talk to us. We have to talk it out. If you keep it in, you’ll get depressed. Nothing you say is going to shock us anymore. We’ve already read the worst of humanity.”

My supervisor and I would talk over the kinds of things they’d read about. We’d monitor to ensure the new person wasn’t working on cases with heavy sexual abuse. One time, a coworker walked out after their first trafficking case. None of us saw them again. Many coworkers save myself and one other left work early because a case they worked was too horrific.

The work I did was as a writer for immigrant victims of Domestic Abuse (VAWAs), Trafficking (T-Visas), Crimes (U-Visas), and the dreaded Asylum case. There was a rule in my home that I wasn’t allowed to talk about cases, especially trafficking and domestic abuse cases.

If you will permit me, we’re going to discuss that today.

As I’m sure you’re well aware, a film has come out that tells the story of an abusive relationship. You wouldn't really get that from the trailers, or from how Blake Lively talks about it, and how everyone now talks about Blake Lively. There are of videos where girls say “Get ready with me to go see It Ends With Us” and they pile on florals. It’s almost too self aware.

Most of the conversation surrounding the film has little to do with the content, the severity of the topic, and everything to do with Blake Lively. Is Blake Lively a mean girl? Is she an asshole? Who cares? There’s something much more serious at stake here.

How do we talk about abuse? Is abuse only okay if it’s Face Down? Or Pretty Girl? Is abuse okay if it makes everyone cry over fictional characters in a 600 page book on TikTok? Is it okay if it consists of us loving a book and buying character themed nail polish? Is it okay if it means aesthetically pleasing photos on Pinterest? Is it okay if it’s a coloring book? Do we talk about the French woman who discovered her husband drugged her and let many men rape her? Do we never talk about that sort of thing?

If I may.

There is only one way to talk about abuse, though one still has to and still can be considerate of others. You cannot deny it. You cannot dance around it. You have to be straightforward. You have to confront it directly.

First, I want to dismantle the idea the Domestic Abuse is purely physical because this sets back too many people. When things get physical is when things get critical. A person doesn't just wake up one day and decide to punch their spouse.

It typically starts slow. Usually it’s Psychological Abuse, then Verbal, then it spreads. I had a case where a woman experienced a miscarriage, and in the year that followed she got more and more abusive towards her husband (whom she blamed for the miscarriage) and eventually chased him around with a knife in an attempt to stab him. She then slashed his tires so he couldn’t escape her. Eventually, he had to run away to another state and cut off ties with everyone he knew for his safety. How did he get to this point? It started with arguing, name calling, refusing to hear him out, cutting out his connection with people, accusing him of cheating, keeping tabs on his every move, following him to work, and soon it escalated.

Do you hear this story and want to buy nail polish based on the victim I mentioned? No? What about a coloring book illustrating his story? No??? No takers????

The problem isn’t that we can’t talk about domestic abuse or even depict it in media, the problem is how do we take responsibility and have maturity about this topic. Is it ethical to roast the fashion of a character meant to be an abuse victim’s fashion sense? Are domestic abuse victims only worth their salt if we like their fashion on camera? Or to have a ‘Girls Night Out’ where everyone wears florals to go see a film about domestic abuse tee hee? Is it okay if we sing a song to it that’s low-key catchy? If all depictions are wrong then is Sara Bareilles wrong for her portrayal in the musical Waitress? (I’ll answer that one: NO.)

I explained to someone that the reason why people think domestic abuse is only domestic abuse if a man beats his wife is because we’ve normalized everything else, and it’s easier to sensationalize physical abuse. It’s easier to say the song What’s Love Got To Do With It? is catchy, it’s not easy to ask ourselves the deeper questions about why so many black women are subjected to domestic abuse and not given the proper help they need to escape and find healing. Tina Turner is a name many of us know well, and she was still abused and tried to hide it. Rhianna is one known better in recent memory. What does that tell us about ourselves? About how we are lacking in supporting women, the foundation of our societies? But women are not the only ones subjected to abuse. We can have a fun pink filled film meant to show how the patriarchy hurts both men and women, but are we ready to discuss how men can face domestic abuse as a result of the patriarchy and at the hands of other men and/or women? Are we ready to hear their stories, or will we be dismissive like we’ve been told to be?

On March 9th, 1977 Francine Hughes set her long time abuser and husband Micky on fire. She watched the house burn, destroying the man who made her life a living hell. It started thirteen years prior when she first married James “Mickey” Hughes. Throughout their marriage, Francine was victim to physical, verbal, and emotional abuse. I don’t think it’s been stated, but if she’s experienced those forms of abuse, she likely also experienced financial, psychological, and sexual abuse as well. I’ve never read a case where everything else was bad but their sex life was perfect. Eventually, the two were divorced, but that did not save her from his torment.

Prior to the night of the murder, Micky beat Francine in front of their children, destroyed her textbooks on secretarial courses, and threatened to kill her if she did not have sex with him. We can only imagine Francine’s horror at realizing that though they were reaching for a divorce, the abuse was not over. It wasn’t just about her, it was about her children.

It’s important to note that Francine called the police who refused to help her. Even though they heard Mickey’s threats, they still did not help her. Francine Hughes’ case went on to be a landmark case, but many advances in societal understandings of abuse took years and still have years to go to reach a public understanding.

In the case of my clients, they were immigrants, many illegal. What was supposed to be a loving marriage turned into a power struggle and chance to domineer someone because of their immigration status. They often believe no one will listen to them because of political rhetoric and their abusers telling them no one will protect them if they’re illegal. There is no escape for them. Actually there is, but they don’t know that.

How do we talk about this hideous side of humanity? How we do depict it in art?

With the truth.

Ana Mendieta was born in Cuba in 1948. To escape Fidel Castro’s revolution, she and her older sister Raquelin (15, Ana was 12) were sent to the United States through Operation Peter Pan. They migrated in 1961, ending up in Iowa of all places. Fortunately for them, the sisters weren’t separated. In this strange new land, they spent their first weeks in refugee camps then to several institutions and foster homes. Mendieta would be sent to an orphanage run by nuns, which she described as cruel and abusive. It wasn’t until 1966 that she was reunited with her mother and younger brother, and not until 1979 that she would be reunited with her father.

From a young age she knew she wanted to be an artist. Though she struggled with learning English, she was able to go to college and even earned both a BA and MA. In light of the growing feminist movement, often times Mendieta is looped in as a feminist artist when in fact she did not like the title of feminist. This doesn’t surprise me given the exclusivity of the feminist movement (even today) and her feelings of isolation given her migration from Cuba. Much of her work explores the idea of a motherland and making our mark in the land to become one with nature. While this work is incredible, it’s not the area I’ll be focusing on today.

The idea that I’m writing about an incredible and versatile artist like Ana Mendieta and I have to bring in her terrible husband doesn’t sit well with me. When one looks up Mendieta we’re confronted by constant videos describing her death, especially given that her ex-husband passed this year. I’m not a fan of true crime for a myriad of reasons, the least of which is the questionable ethics. (or maybe that is the biggest reason) But for this topic, we have to discuss her marriage to Carl Andre.

Before we get to Carl Andre, let’s discuss Mendieta’s art.

I’m not going to share the artwork for Rape Scene 1973, but it perfectly illustrates Mendieta’s awareness of violence towards women, and is something of an omen of things to come. In 1973 a female student was raped and murdered at the University of Iowa by another student. Mendieta was a student at this time, and became destressed at the last of effort by law enforcement and the school with regards to the rape.

She construction her piece, Rape Scene, in which she invited friends to visit her in her Moffit Street apartment, leaving the door slightly open as if they stumbled upon the scene by accident. When they walked in, they witnessed Mendieta nude from the waist down and covered in animal blood (a common motif in her work) (there were many slaughter houses in Iowa for her to get bovine blood from), tied to a table and bent over. Mendieta did not move, reenacting the rape and murder of her fellow student. The piece lasted an hour.

“Mendieta's corporeal presence demanded the recognition of a female subject. The previously invisible, unnamed victim of rape gained an identity. The audience was forced to reflect on its responsibility; its empathy was elicited and translated to the space of awareness in which sexual violence could be addressed.” - Kaira Cabañas

There is a photo you can see of it, but I’m warning you that it’s not easy to look at.

So we see from an early age that Ana Mendieta was not just aware of violence towards women and the systems in place that failed to protect them, but she took them head on as a passion project. Throughout her life she was an activist who worked to reunite Cuban families and help victims of domestic abuse.

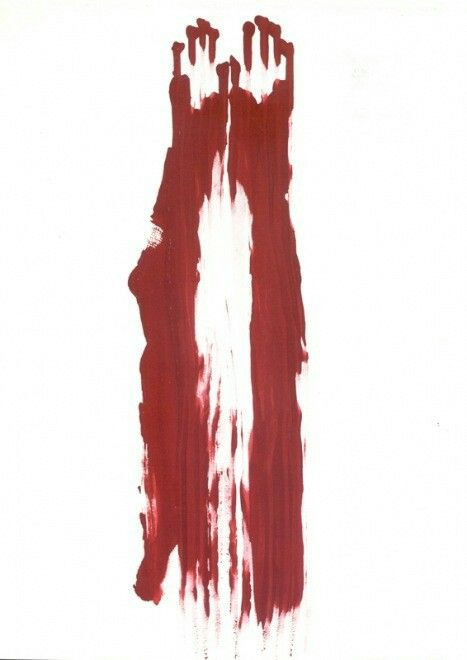

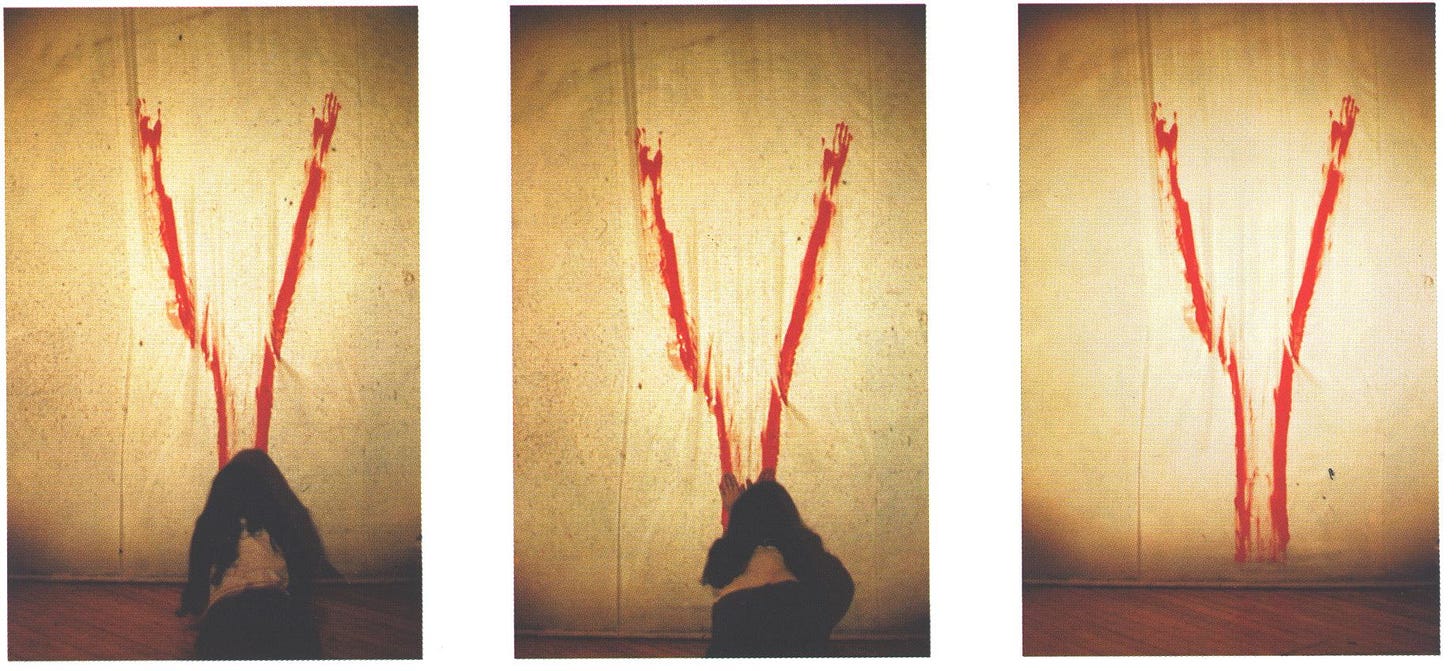

What I find most alarming of her work isn’t actually Rape Scene but Body Tracks. Body Tracks is among some of her more famous pieces, partially for its use of blood.

“Drawing from the Afro-Cuban religion Santería, Mendieta uses animal blood and tempera paint to create imprints of her hands on white paper. She repeats this ritualistic gesture in silence throughout the performance, forming variations of her silhouette. Mendieta exits the gallery space, leaving behind her body prints for the audience to bare witness to the red markings in her absence. Together these acts can be interpreted as Mendieta’s political stance against violence inflicted upon women.” - Hemispheric Institute

It’s easy to see why this is so compelling. When you watch the videos, you quickly become aware that Mendieta take this work seriously. She approaches the canvas and ever so slowly moves her bloody hands down, only to then walk away. It’s agonizing to watch, but what struck me the most was the way in which she just stepped away like it was nothing. It’s as if this brushes it off, ready to move on.

This is actually intentional on Mendieta’s end. She’s dismissive of the blood, moving on to the next violent act. It reminds me a bit of Gabby Petito. Living in Utah while that was happening, there was a cosmic energy in the air. Everyone was asking question, everyone wanted to know where she was. It was as if everyone turned their eyes to the campsites in the west in search of Gaby Petito. And once she was found, and her fiancé disappeared and committed suicide, suddenly it was washed away. We all forgot about her. I never heard her name again.

Mendieta confronts this in her work. She walks away as we walk away from the news, whether that’s a French woman who discovered her husband was not the ‘good husband’ she believed him to be, a young girl who converted a van to travel with her fiancé that killed her, Ukraine’s continued war with Russia, Palestinian children dying, or a promising artist who ‘fell’ from her apartment window to her death.

Ana Mendieta met Carl Andre in 1979. They entered into a relationship despite their 13 year age gap. Andre had been married and divorced twice and married Mendieta on January of 1985. Their marriage was tumultuous, which Mendieta certain that he was cheating.

At this point, Mendieta’s career was truly starting to take off, whereas Andre had already been cemented as a well loved and recognized minimalist sculptor. Yet, on September 8th, 1985, Mendieta died after falling from her 34th floor apartment she shared with Andre in Greenwich Village. A witness reported to hearing fighting and a woman screaming, “No” before a loud south. Andre appeared to have scratches all over this faces and there was furniture turned over in the apartment. Mendieta was planning to divorce him.

What we do have is a recording of Carl Andre’s 911 call in which he states “My wife is an artist, and I'm an artist, and we had a quarrel about the fact that I was more, eh, exposed to the public than she was. And she went to the bedroom, and I went after her, and she went out the window." Andre was arrested for second degree murder, but his lawyer argued Mendieta’s death was most likely an accident or suicide. The judge, who acquitted Andre and was set free, admitted that Andre “Probably did it.”

There’s something haunting about the artist who pushed back against violence towards women dying a horrific violent death. There are no indications that Mendieta was suicidal, nor any evidence of prior examples of suicidal ideation from her. Carl Andre lived until January of this year, dying at the age of 88. Ana Mendieta was 36 when she died.

Am I saying Carl Andre killed her? Well, I can’t. I know he’s passed but I’d like to not get sued. What I’m saying is what I’ve seen again and again and again, which is that if anyone killed her, it was her abusive husband. And yes, I do believe he was abusive. Andre was back and forth on his statement, denying and changing the story.

The trial used Mendieta’s Latina ancestry as a backdrop to a possible suicide. The defense pointed to her ‘Latina temper’ and alcoholic tendencies to turn the argument away from Carl Andre. (fyi this is circumstantial evidence at best and also super racist) Ana Mendieta’s work and use of blood and violent depictions was used in the trial to suggest Mendieta’s potential suicidal ideation as well as mental instability. All pieces of evidence have been sealed and Carl Andre was the only person able to unseal them.

Carl Andre would go on to have a successful career. Mendieta, while largely left out of the art history narrative, has a loving family that fights for her to be remembered. Though not supported by her family, a tv series by America Ferrera is being made about Mendieta. A recent book by Xochitl Gonzalez titled Anita de Monte Laughs Last was published this year, inspired by Ana Mendieta. In 2016 women in London protested the addition of Carl Andre’s work in support of the memory of Ana Mendieta. With our effort, though she has passed, her work can live on.

So how do we talk about Domestic Abuse? How do we honor Ana Mendieta, Gaby Petito, Tina Turner, Francine Hughes, and the countless other victims who cannot speak up? We speak raise our voices. We say, “Enough is enough.” We provide the means to help them escape, to build better lives. I wrote their stories day in and day out, I took on their voices to help them gain freedom, and I knew that was not enough. My clients were immigrants like Mendieta. They were the lowest of the low, denied everything.

I’m gonna go back to Cherry Wine. If you haven’t seen the music video, it’s an excellent video featuring Saoirse Ronan, and downloads for the song go to benefit domestic abuse charities the world over. In the video, we see as Saoirse slowly takes off her makeup between scenes of romance and joy she shares with her partner. It is only when the eye makeup comes off that we realize she is hiding a bruise he then tries to hide with her hair. The lyrics tell the story of a man being abuse by his female partner, a perfect juxtaposition. We never see the violence, but we see the pain, the bruising, the love, the laughter, the good and the bad. We get the hint that her partner must gaslight her into staying, denying her pain.

I’m not saying there shouldn’t be films about domestic abuse. Or that we cannot take it head on. Angela Bassett’s scene as Tina where she looks in the mirror and sees how Ike has destroyed her is one that should not be forgotten. I’m a Millennial, I’ll never forget when I saw the images of Rhianna after Chris Brown attacked her. I’ve never seen Glee or Supergirl, but I remember when Melissa Benoist revealed that she was a victim of domestic abuse (and showed up with a bruise she lied about on live tv). While Bassett’s example is a depiction, all of these are real events. And that doesn’t count the real life examples from people I know and love who have also been victims of abuse. If we silence this conversation, we’re playing the hands of the abusers, not the victims. Yes, we can be careful. Yes, we can be responsible. Yes, we can be mature. But most importantly, we can’t hide it. We can’t shove it under the rug. We have to say it. OUT LOUD.

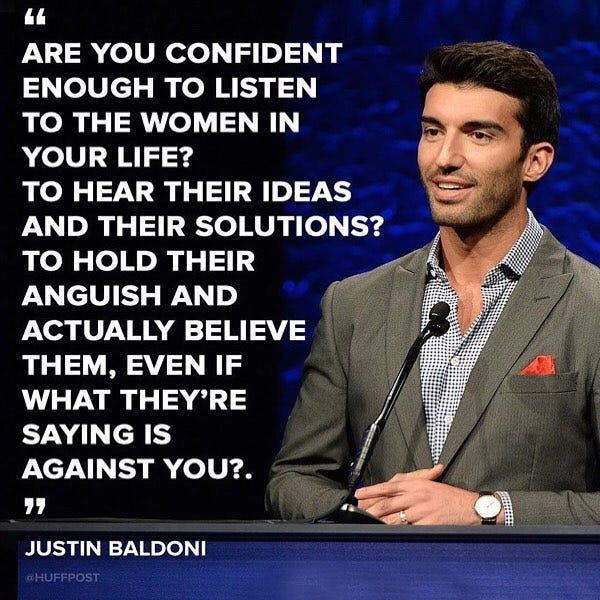

I wanted to share one last thing, which is just how incredibly wonderful Justin Baldwin is. For those not aware, he started Man Enough where he challenges traditional and toxic views on masculinity, and has used his work on It Ends With Us to advocate for women and discuss domestic abuse. I recommend his Ted Talk from 2018. I hate that instead of focusing on a man trying to do good, we’re focusing on petty drama from a woman who may or may not be a mean girl. We can do better.

I learned a lot in my time working with domestic abuse victims. I miss it so much, especially the wonderful people I met and worked with. Despite everything they went through, nearly every client we had seemed so optimistic for the future. They believed this was not the end, that their lives were meant for more. They inspired me every day to keep going, to believe in something better, and to strive for the best. How do you come out of a harrowing situation and still manage to smile? One day at a time. One step at a time. One breath at a time.

Wow. A torrent of insight and righteous anger. I am much older than you and not up to speed on all the cultural references, but powerful writing transcends this sort of detail.

Powerful and utterly heart-breaking in equal measure. Especially given the news this week of the Ugandan runner from the recent Olympics who has been killed too.

I truly wish none of these stories had to be told, because they just shouldn't happen. But you do a really amazing job writing with such passion and compassion.