100 Years of Surrealism

A month-long celebration of the Surrealist Movement starts today with a little backstory

“So strong is the belief in life, in what is most fragile in life-real life, I mean-that in the end this belief is lost.” - Andre Breton (The Surrealist Manifesto)

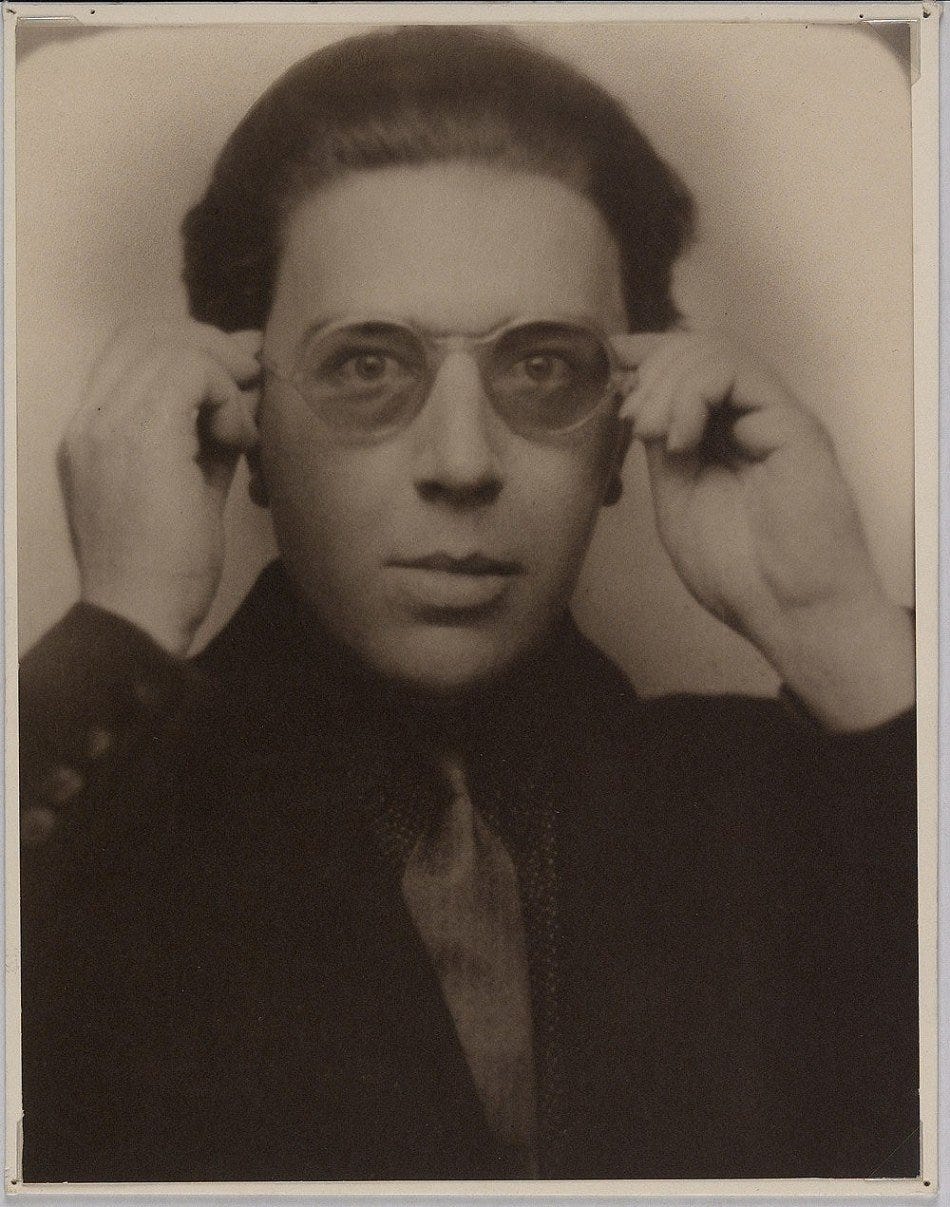

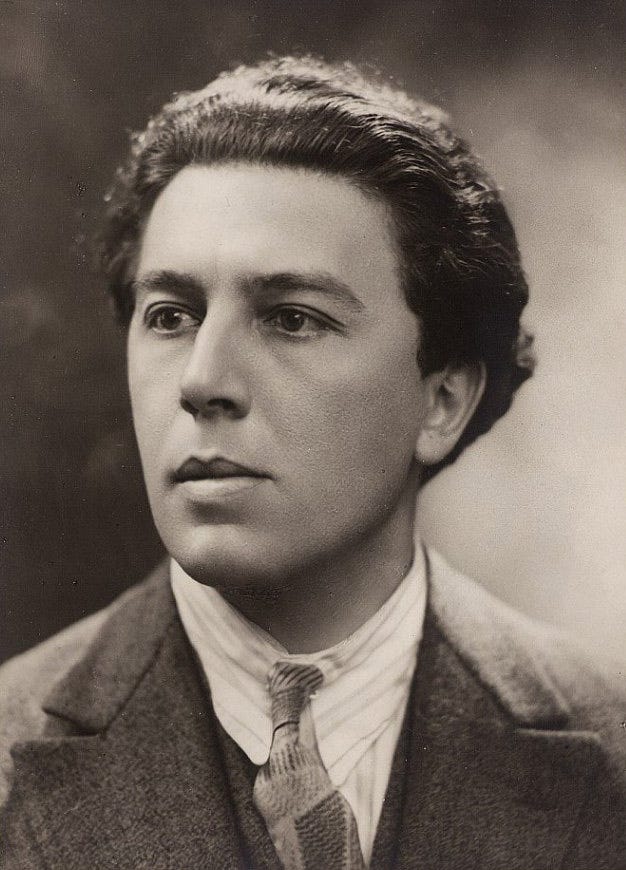

100 years ago Andre Breton published the Surrealist Manifesto and kicked off a movement that changed history. He would go on to add to the manifesto and even write a second one, maintaining his place as the head of the Surrealist Movement that changed art history and media forever. We can only speculate as to whether or not Breton was aware of how his manifesto would be the catalyst to one of the most important movements of the 21st Century, but we have the privilege to look back on 100 years since and see the ripples.

Surrealism is still influencing our work today. Surrealism echoes into our everyday subconscious, just as it wishes to. Many surrealist and surrealist adjacent (we’ll get there) artists are still recognized and revered by the greater public. And media that is consumed by the every day person is still influenced by the Surrealist movement. In essence, Surrealism is still alive and breathing. And it’s not going anywhere anytime soon.

But let’s step back. Why Surrealism? How did it happen?

Surrealism came into the world at a crossroads in human history. WWI had ended, but left a long shadow over the soldiers who fought. Andre Breton was a medical student interested in psychology and helped to care for wounded soldiers on the battlefield. It would be here that he came face-to-face with a strange psychological phenomenon known as ‘shell-shock,’ or what we today called PTSD. Our understanding of PTSD is still limited 100 years later, but the desire to know more was a mere seed in Breton’s time.

Despite its original publication being in 1899, Sigmund Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams and much of his theory regarding psychology entered into public canon following WWI. And Andre Breton, poet and psychology student, was quickly drawn in. He would even meet his hero Freud, and references his ideologies in his manifesto.

It’s important to note, before going into Freud’s work, that many of his ideas have been proven wrong, or questioned due to their lack of scientific research to back them up. Nearly everyone to this day knows Freud. That’s incredibly, really. If we call someone ‘anal’ for being a stickler, we’re referencing Freud. We still use the term ‘Freudian slip’ (a guy once insisted I made one and that meant I secretly wanted to date him) (spoiler alert: we did not date), and we’re all uncomfortably aware of Freud’s oedipus teachings.

Much of this is due to the fact that Freud is still taught. Why is he still taught if his theories have been largely proven wrong? Well, it’s important to understand that Freudian theories have helped to develop much of modern psychology as a whole, but because of its popularity and in order to dismantle it, one must first understand it.

If you’re wondering, yes, I have been studying up on Sigmund Freud to write on the Surrealists. To understand the Surrealists and what Andre Breton was trying to do in leading the movement, we have to understand Sigmund Freud.

I find it incredibly charming that Breton used his medical knowledge (if you can call it that) to inform his creative endeavors. It gives me the sort of joy that reading When Breath Becomes Air does (though they couldn’t be more different) (Surrealism, for all its worth, hasn't made me cry the way WBBA did). Perhaps a more fitting contemporary comparison would be the book Your Brain on Art. For any that haven’t read, it’s a look at how art in varying forms affects neuroplasticity and it’s fascinating.

Surrealism, namely through the Surrealist Manifesto, is steeped in Breton’s psychological background. You cannot have one without the other. I started reading it and quickly realized I didn’t understand a damn thing. I’m prideful, and I believe in my comprehension more than anything, so for me to stop and admit I needed to back up and study up first isn't easy to admit. It means I really didn’t get it.

Freud theorized what he called the tripartite, a sort of explanation into the subconscious vs conscious state. Of this, there are three parts: the Id, Ego, and Superego.

The Id is the subconscious that aims for desire and needs. According to Freud, this shows first in infancy. Infants do not exhibit signs of Ego and Superego, which come along with age. The infant, under Id, is only consumed by their desires. They cry not with thought to how that effects those around them, but solely for their needs. All they know is what they desire and are driven towards. We are by nature unaware of the unconscious mind as it is a natural part of our being. Yet, we are aware of our innate desires such as hunger or sexual drives.

Then we have the Ego. The Ego develops in early age, acting to control the Id and thereby direct and maintain appetites. An analogy used is that the Id is the horse, and the Ego is the driver guiding the horse.

Finally, we have the Superego. This is something like the idealized self. This is the perfect idea of oneself we aspire to. When we are led by the Superego, which is by nature unattainable, we become unsatisfied and even feel guilt for our actions and lifestyle. The Superego is what I like to call ‘the Pinterest self,’ the part of us we want to curate into a gorgeous image that isn’t lead by Id and is a natural component of the Ego.

It wouldn’t be strange to argue the surrealists viewed society in the 20th Century as part of the Superego, and they were aiming for the Id. It is this carnal self, the side of us that exist without morality and without idealism, that drew the Surrealists in. What they seek is the sublime, the world without words, where things are undefined. They seek the marvelous, they seek the world of dreams.

How remarkable that Surrealism can encapsulate so many areas: painting, photography, sculpture, poetry, novels, film, and even fashion. And through all of these mediums, the artists that made up the Surrealist Movement carved a new reality.

Breton wrote:

“I believe in the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality, which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality, if one may so speak. It is in the quest of this surreality that I am going, certain not to find it but too unmindful of my death not to calculate to some slight degree the joys of its possession.”

Okay, Andre, you may be on to something. There’s no question about Andre Breton’s writing talent. So where does Surrealism take us? We now understand some of the Freudian logic that leaks into the movement, but what was Andre Breton seeking as he lead the movement?

Breton's is seeking the marvelous. “[The] marvelous is always beautiful, anything marvelous is beautiful, in fact only the marvelous is beautiful,” he writes. It is to creating the beauty, and then to embrace death. “Surrealism will usher you into death, which is a secret society,” he later states. Slightly morbid, but anyone who has seen Surrealist work knows death isn’t a far off concept. So can we find the morbid and the marvelous in one image, one sculpture, one poem, one photograph? And what is the makeup of this strange image we seek?

Surrealism’s most common characteristics are the following:

Interpretation of Dreams - Freud believed that dreams could contain aspects of the Id that had been tempered down by the Ego and Superego, that the Id was trying to reveal hidden truths through dreams. This stems from his work studying Anna O in which she could not acknowledge any trauma while awake and alert. This idea is found everywhere in Surrealism.

Automatic Writing - I’ll never understand this, I’m a chronic editor. The Surrealists, namely the writers, aimed for a direct and unedited approach to their writing, seeking a more organic voice that defies the Rationality that was reigning supreme.

Denial of Morality and Convention - Since Morality and Convention are, according to Freud, products of the Ego and Superego, naturally the Surrealists sought to opposed this. This takes on many conventions, but is also a major flaw of the Surrealists as a peoples. Defining convention, for example, does not mean opposing misogyny or accepting homosexuality (more on that in another post). The Surrealists were largely straight white men, their denial of Convention meant denial of religion (namely Catholicism), open relationships, and a contention with capitalism (however it should be noted Breton himself left the Communist Party). They opposed the strictures of 20th Century society at large.

Juxtaposition - My personal favorite! Surrealist work often shows a strange contrast. This is even true in Surrealist fashion (yes, we’ll go there). Strange objects that shouldn’t mix are mixed, providing a sense of humor but also a question into what is rational. Why can’t a lobster also be a telephone? Who said it can’t? Why can’t a shoe be a hat? Why not?

Morbidity - This is one you may have to squint to see. It’s not that Surrealists are obsessed with death, but there is always an underlying sense of it. When Leonor Fini paints her favorite writer, she paints him without clothes, exposing his muscles and bones. Magritte painted images of people with their faces covered, a possible reference to his mother’s suicide (more on this later). The surreal must always be on the edge of death to truly be marvelous.

Breton not only lead this ideology, but also served as its judge and executioner. To become a true Surrealist, one had to earn Breton’s approval. This was not a democracy, for all that the Surrealists were certainly political. One could argue Breton’s genius justified this, and I’m sure we would all agree with his criticism of Dali (if not, I’m concerned), but whether you like Breton’s leadership or not, he’s the spirit of Surrealism. But don’t worry, we have plenty of time for gossip. And trust me, there’s plenty of juicy gossip among the surrealists. Pull out the tea, don your chismosa spirit, and get comfortable.

If it isn’t obvious, for all that Surrealism is deep and a byproduct of psychological study, it’s also incredibly fun. For the next month we’ll be exploring Surrealism. I’ll be sharing about various artists, including contemporary surrealists to show how in many ways the movement is still alive and thriving. I hope you’re excited and ready. We’re going to have a lot of fun. We’re going to have a marvelous time. (ba dum cha!)

A note

The most famous Surrealist is Salvador Dali. Unfortunately, I absolute HATE Dali. He was a fascist who supported not only the Nazis (though this is sometimes argued to be humorous), but Francisco Franco (that one isn’t a joke). Dali was also a certified creep with women. The only time I’ve liked him was when Adrian Brody played him in Midnight in Paris. We will NOT be hearing any more on Dali. I apologize if you wanted to hear about Dali, but there’s plenty out there about him.

Another artist I will not be writing on is Frida Khalo. This is not because I dislike Frida. Uh, no. I love Frida. I have Frida themed clothes. First off, Frida didn’t like the Surrealists. Second, see this quote:

“They thought I was a Surrealist, but I wasn't. I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.” - Frida Kahlo

Frida did not consider herself a Surrealist, so we will respect that. While I understand that many art historians have, I’m sticking to my guns on this one. We’ll talk about Frida, I promise, but not in relation to Surrealism.

Pablo Picasso is sometimes linked in with the Surrealists, but he never officially joined. It’s also important to note that some Surrealists were in and out, namely Dali and Magritte. Dali for the reasons I listed above, Magritte for different reasons (and I agree with Magritte personally).

Most of the artists we will be speaking of are women, because I prefer the women of Surrealism. I will also be sharing literature, film, and fashion. If the last one sounds strange, my goodness you’re in for a surprise.

We’ll continue this conversation on Friday, in which I will gush about a Surrealist television show from the early 90s and the creators link to my beloved Philadelphia.

Such an interesting opening to the series, Luka.

I've read a fair bit of Freud over the years, (though personally always gravitated much more towards Jung's writing.) But I actually had no knowledge of how Freudian ideas leak into surrealism so much, nor did I know of Andre Breton's background as a psychology student too.

So thanks for this.

(p.s Also, I have to say I totally relate to what you say about Dali too. He's someone I've never been able to bring myself to feature on Art Every Day either!)

Thanks for your article, I also find Dalí repulsive, and he was, apart from a fascism supporter, what we call in Spanish a "chaquetero". Chaquetero comes from chaqueta, which means jacket. A Chaquetero is a person who changes ideology capriciously when it benefits them personally (they change their jacket shamelessly). So Dalí was among progressive people, then he was progressive, and when Franco did the coup and won, then he became a fascist, cause it was more convenient. It's almost even worst, cause he was an oportunist motherfucker. Even his works I never liked, they looked like a copy of Ives Tanguy. Anyways another surrealist I love is Max Ernst, although I think he was an asshole with women, as almost all of them in that period sadly. I have no idea about his connection to surrealist movement though, but his work speak to me deeply. Thanks for your article and giving Freud some credit :)